Coalition vying for federal funds to create a hydrogen hub

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

David Roberts, chief innovation officer at the Indiana Economic Development Corp., is spending a lot of time right now focused on hydrogen.

That’s because the IEDC, along with numerous public and private partners, is hoping to land big federal funding to establish northwestern Indiana as one of a handful of hydrogen hubs planned around the country.

“I’ve been on four hydrogen calls yesterday, I’ve got a few hydrogen calls today,” Roberts told IBJ on Oct. 21. “It’s getting really dynamic here.”

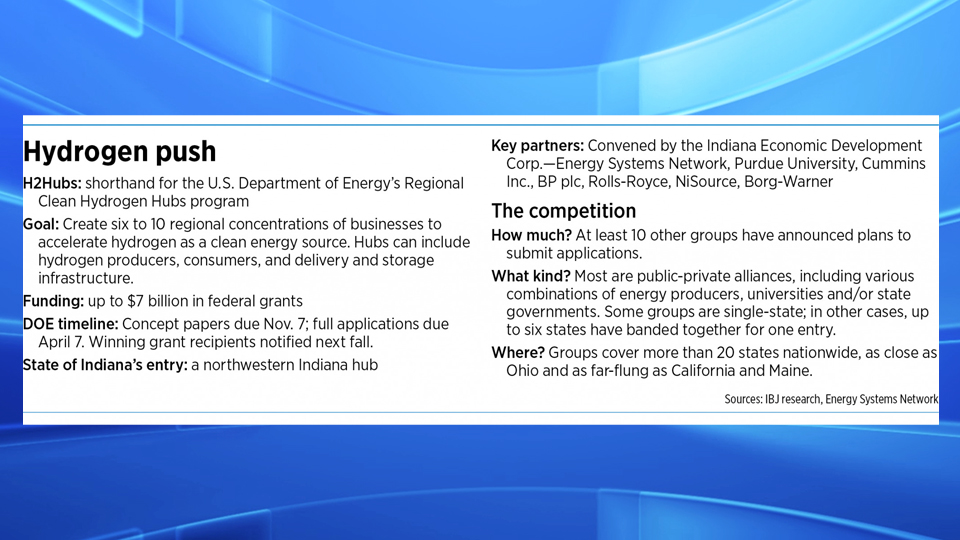

The Indiana coalition—which also includes Indianapolis-based Energy Systems Network, Columbus-based Cummins Inc., Purdue University, London-based BP plc and others—is vying for a portion of the up to $7 billion the U.S. Department of Energy is making available in its Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs, or H2Hubs, program.

The funding comes from the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed late last year. The application deadline for concept papers is Nov. 7, and the Department of Energy will respond by the end of the year to applicants and either encourage or discourage them from proceeding. Deadline for submitting full applications is April 7.

The Department of Energy has said it expects to select six to 10 hydrogen hub projects, with winners notified next fall.

According to the DOE website, projects should focus on clean hydrogen, which refers to how the hydrogen is produced. Among other methods, this can include hydrogen produced using renewable-energy sources such as nuclear or biomass. It can also include hydrogen produced with fossil fuels if the resulting carbon emissions are captured and sequestered.

The hubs should demonstrate the production, processing, delivery, storage and end-use of clean hydrogen, the Energy Department said.

Among other deciding factors, the department said it intends to select projects that represent different regions of the country, different hydrogen production methods and different end uses for the hydrogen, including electric power generation, industrial uses, residential and commercial heating, and transportation.

Because the hydrogen industry itself is in its infancy, certain other details about the H2Hubs program, including what the Indiana hydrogen hub might involve, are not yet set.

But those involved in Indiana’s H2Hubs efforts say northwestern Indiana would be an ideal place for a hub that would help kickstart the state’s hydrogen industry.

Indiana’s geology, particularly in northwestern Indiana, includes natural caverns that could be used to store captured carbon dioxide underground as a way to reduce carbon emissions, said Energy Systems Network CEO Paul Mitchell.

Northwestern Indiana also has a concentration of heavy industry, such as the BP refinery at Whiting and steel mills operated by U.S. Steel in Gary and Cleveland-Cliffs in Burns Harbor and East Chicago.

Likewise, that part of the state sees a lot of transportation activity from the trucking industry, the Port of Indiana at Burns Harbor, and nearby Chicago and other cities.

Heavy industry and transportation are strong potential customers for hydrogen sales as companies look to shift away from fossil fuels and reduce their carbon emissions, Mitchell said.

“We saw that [storage capacity and density of potential hydrogen users] as really being a compelling collection of assets that could compete with anyplace else in the country,” he said.

That’s why it makes sense to focus early efforts on that part of the state, the IEDC’s Roberts said. Once hydrogen activity catches on there, he said, it should accelerate hydrogen-related efforts statewide.

Getting funding for a hydrogen hub could help Indiana become a leader in an emerging industry, he said. “That’s really what’s helping motivate our interest here.”

The state of Indiana has also taken steps to position the state for the emerging hydrogen industry.

Last month, Indiana was one of seven Midwestern states that signed a memorandum of understanding aimed at supporting hydrogen production in the region. The other states participating in the effort are Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin.

Also this year, Gov. Eric Holcomb signed legislation that creates a regulatory framework for companies to store captured carbon dioxide underground.

Who would pay for it

The H2Hubs program requires that grant recipients provide a local match of at least 1:1.

Roberts said that, should Indiana be chosen as a hydrogen hub site, he would expect the grant award to be in the range of $500 million to $1 billion. It’s too early to say how much the state might contribute to match this amount, he said, but most of the money would come from the Indiana investments made by the hub’s corporate partners.

The IEDC has talked with corporate partners that have specific hydrogen projects in mind, Roberts said, but confidentiality agreements prevent him from sharing details.

Indiana is choosing to take its cues from its industry partners on the H2Hubs project, he said, because those companies are best positioned to know where the technology is headed and what investments are wisest.

That’s an approach that makes sense to State Rep. Ed Soliday, a Republican from Valparaiso who represents northwestern Indiana. Rather than the government’s imposing its own ideas about emerging energy sources, he said, “the marketplace needs to speak.”

Soliday is co-chair of Indiana’s 21st Century Energy Policy Development Task Force. The group, which was formed in 2019 to identify energy policy recommendations that focus on the affordability and reliability of the state’s future electric utility service, released a draft report last week.

One of the report’s recommendations is that state lawmakers, the Indiana Office of Energy Development and the Indiana Department of Homeland Security work with local government and industry to develop safety-related best practices surrounding emerging energy technologies, including hydrogen facilities.

Speaking to IBJ before the report’s release, Soliday said hydrogen seems to show promise, especially as a fuel source for heavy trucks.

“The more you look at hydrogen, the more you’re like, ‘You know what? That’s pretty encouraging stuff,’” he said.

Jump-starting an industry

For its part, Cummins said it’s involved with the Indiana effort—and several other hydrogen hub proposals around the country—because it makes good business sense.

“We want to promote the adoption of hydrogen across the United States,” said Neil Banwart, a program director at Cummins. Banwart works in the company’s New Power segment, which includes hydrogen.

Cummins, which built its name on diesel engines, began ramping up its investments in hydrogen several years ago, investing hundreds of millions in the technology since 2019. Hydrogen currently represents a tiny part of the company’s business, but its lineup includes products like hydrogen fuel cells that can power vehicles, and the electrolyzers that produce hydrogen.

Cummins also has a 50/50 joint venture with NPROXX, a Netherlands-based company that makes high-pressure hydrogen storage tanks.

The hydrogen industry is at such an early stage, Banwart said, that there are few fuel-cell trucks on the road, and those that do exist are part of pilot programs. As a result, a fuel-cell truck can cost two to three times what a diesel truck costs, and the per-mile fuel costs for hydrogen are also multiple times higher than for diesel.

Those costs will inevitably come down as hydrogen gains traction, Banwart said, but “right now we do need federal money to make this all work.”

The hubs can play a key role in accelerating that adoption, he said. “As Cummins, we cannot do this alone.”

Likewise, Energy Systems Network’s Mitchell said that, though the Indiana hydrogen hub proposal focuses on a particular part of the state, it would be a mistake to think of the project only in those terms.

The hub would likely span multiple states along the Interstate 90 corridor, he said. “The hydrogen markets that we’re talking about, they don’t begin and end in any one state.”

Mitchell also said Indiana’s hydrogen industry will continue to evolve, whether or not it receives H2Hubs grant funding.

The competitive landscape

One big unknown at this point is the scope of competition Indiana will face.

At least 10 groups around the country have announced their intent to apply for H2Hubs funding. Partners in those efforts include universities, companies and representatives from more than 20 states. Those states are as close as Ohio, Minnesota and Wisconsin, and as far away as Washington state. A group led by New York state includes participation from five New England states.

Mitchell said he believes many others are working quietly on their own applications—perhaps up to several dozen.

But Indiana is so optimistic about its chances that it will start working on its full application as soon as it submits its concept paper next month. It won’t wait to get feedback from federal officials, Roberts said, because Indiana’s planners feel the state’s application is strong enough that it’s sure to pass to the second stage.

“We’re pretty confident that this is a positive project.”

Damian Bilbao, BP’s Denver-based vice president of U.S. low-carbon ventures, is also bullish on Indiana’s prospects as an H2Hubs competitor.

BP is still investigating what its future hydrogen investments in Indiana might look like, he said, but the company has taken “a very active role” in the state’s H2Hubs effort.

Northwestern Indiana’s concentration of heavy industry, its carbon-storage capabilities, its focus on real-world projects and its collaborative approach will make it a strong competitor for H2Hubs funding, Bilbao said. “We think it has all the characteristics to distinguish itself nationally—and, globally, frankly.”