Startup Could Hold Final Piece of 3-D Printing Puzzle

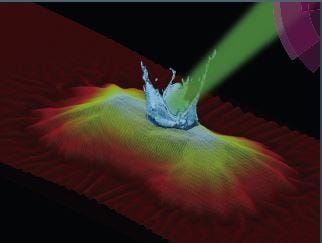

The company uses laser manufacturing processes.

The company uses laser manufacturing processes.

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAn Indiana startup says it’s going to “cut through the hype” surrounding a new trend in manufacturing. The excitement centers on 3-D printing technology, a relatively new concept in the industry that involves a type of robot “printing” a three-dimensional object. Guided by a computer, successive layers are laid down until the object is complete. However, Crawfordsville-based Frontier Additive Manufacturing says a problem lurks within those layers that compromises the quality of the finished product. It’s a glitch that has puzzled engineers and stunted the adoption of 3-D printing, but the startup says it’s cracked the code to unleash the method’s true potential.

Frontier Additive Manufacturing Co-founder Eric Lynch says 3-D printing has mostly involved plastics, but—hence the company’s name—the startup is focusing on the new “frontier” of metal 3-D printing. The method is called metal “additive” manufacturing, as opposed to subtractive, which is the traditional way of grinding down chunks of metal into parts. Metal additive manufacturing, however, has been hindered by micro-fractures, or tiny breaks, that occur within the metal as an inherent part of the process.

“Metal expands when it’s hot and contracts when it’s cold,” says Lynch, who also serves as chief executive officer and president. “To make a substantially-sized part, you’re going to have hundreds, if not thousands, of layers that are about the thickness of a piece of paper. As you’re adding material from the [bottom] where you started, it’s going to be many hours old and cold when you’re adding [finishing layers]. As that metal’s contracting, it’s putting stress into that part that can overcome the strength of the metal and break it.”

The result of this thermal stress is a part that’s about half the strength than one that’s traditionally made. Often used to make replacement parts, the method is producing sub-par parts “that have the quality issue of ‘do we trust this piece or not?’” says Lynch.

Based on the discoveries of Purdue University engineering professors Gary Cheng and Yung Shim, Frontier Additive Manufacturing says it’s solved the problem through a technology that monitors and controls the thermal stress in “micro steps.” Lynch says the method produces metal pieces that use the same amount of material, but are 20 percent stronger than objects that are standardly made.

“Our technology isn’t just monitoring, because there are some monitoring technologies out there,” says Lynch. “We’re controlling the process, not only to correct this micro-fracture issue, but we’ll be able to tune the crystalline structure of the metal to give you the exact metal properties you want.”

Because metal additive manufacturing can also produce lighter weight parts with less material, the aerospace industry has been the first adopters of the technology for weight-saving purposes. It also enables manufacturers to make complex shapes that previously required many parts. Lynch says GE is using the method on a very limited basis to make fuel injectors for its new Leap turbofan engine. He says NASA is also taking advantage of the technology.

“NASA took a rocket engine, that with [traditional methods] was made up of 118 pieces, and made the whole engine in two pieces,” says Lynch. “It reduced the number of potential points of failure significantly. In the space industry, this particular process is very much sought after, because it not only makes lighter weight parts, but you can reduce the number of points of failure too.”

Engine-making giant Pratt & Whitney opened the Additive Manufacturing Innovation Center at the University of Connecticut in 2013. Hoping to work hand-in-hand with the industry’s trailblazers, Frontier Additive Manufacturing was excited to learn it was named a finalist in the Sikorsky Innovations Entrepreneurial Challenge; Pratt & Whitney is the parent company of Sikorsky, which manufactures helicopters.

After owning a small manufacturing shop, Lynch hitched his entrepreneurial wagon to the innovation when he worked at Purdue’s Office of Technology Commercialization.

“When I realized I could get first look at Purdue technologies, I thought, ‘When I find one I can’t live without, I’m starting a company,’” says Lynch. “After nine years, that’s what I did.”

Frontier Additive Manufacturing believes it’s within six months of demonstrating its thermal control technology and already has an Indiana-based medical device manufacturer “actively interested.” Three other pending clients are in the oil and gas, aerospace and automotive industries.

“We’re going to play a key role in the adoption of metal additive manufacturing,” says Lynch. “Right now, there’s a lot of hype; we’re going to cut through the hype and be able to deliver its capabilities. That’s exciting from a technical point of view.”

The company is sharpening its blade, taking aim at perfecting a technology that experts say could revolutionize nearly every sector of the manufacturing industry.