Skin Patch Aims to Help Athletes Detect Dehydration

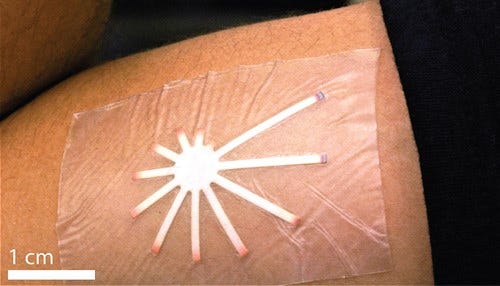

The patch's "fingers" change sequentially from blue to red to indicate the progression of moisture loss.

The patch's "fingers" change sequentially from blue to red to indicate the progression of moisture loss.

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowOrganizers of some of sports’ most elite events are anxiously awaiting a Purdue University professor’s invention. The medical directors of IRONMAN, the Boston Marathon and the Olympic Triathlon have all expressed interest in Dr. Babak Ziaie’s skin patch that monitors hydration levels by changing color—helping protect against dehydration. Noting that conventional monitoring methods are invasive and impractical during athletic events, Ziaie believes the skin patch will appeal to the masses.

“We’ve been bombarded by requests from people to get their hands on this—from the U.S., Philippines, Taiwan and Indonesia. A lot of these folks are athletic directors at universities,” says Ziaie, a professor of biomedical engineering and electrical and computer engineering. “They want to monitor the athletes and improve their performance, get more quantitative information out of the hydration level and correlate that with their performance.”

Ziaie says being just 2 percent from normal hydration levels can affect a person’s cognitive and physical performance by more than 30 percent.

“Coaches who are working with athletes are very interested,” says Ziaie. “They want to optimize the performance of these athletes. Initially, you wouldn’t see this at the gym with the average person wearing it.”

Hydration is typically monitored by weighing a person before and after exercising or measuring urine density. Ziaie says a major benefit of the skin patch is that it provides real-time visual feedback. About the size of the palm of the hand, the patch can be worn on the upper arm, for example.

It’s comprised of a special moisture-wicking paper commonly used in laboratories sandwiched between two layers of medical adhesive. A hole in the center exposes the paper to the skin and allows sweat to be absorbed. A dozen strips extend from the center, each loaded with water-activated dye at the tip.

“All you have to do is look at the fingers that spiral from center,” says Ziaie. “As you start sweating and losing water, the shortest finger changes color first, then progresses to the longer fingers and continues changing color until the whole patch is full of sweat.”

Ziaie’s team is now working on correlating that visual input with actionable information; the group is creating a database to help learn how to “calibrate” the patch to each individual user and their unique hydration needs.

“So the athlete knows, ‘when this gets to the fourth marker, I should drink,’” says Ziaie. “There’s a lot of data processing on the back end, which is also exciting for us, because we think that gives us an edge. Analytics and data are very important these days…we think there’s a lot of new information that might be hidden out there that we can extract.”

Ziaie believes several factors will help the skin patch have a speedy path to market. Among them, the device will not need approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, because it aims to only improve athletic performance, not provide medical information. Ziaie likens the patch’s informational output to the Fitbit, which gives fitness feedback to the user.

The patch could also be scaled up easily, says Ziaie, “using the way they make BAND-AIDs, basically.” The team has manufactured prototypes of the patch using Purdue facilities, and Ziaie believes it could be mass-produced “for a couple pennies each.”

Rather than licensing the technology, the team plans to launch a small startup in the coming weeks to commercialize the patch. Ziaie is aiming to use local resources or grants to move the product to market, such as Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) funding from the National Institutes of Health.

“Our goal right now is to have more people use this and give us feedback about what they want to see and what we should change,” says Ziaie. “It’s an exciting, simple and scalable technology. We’re excited about getting these in the hands of the end-users and providing a low-cost technique to improve their athletic performance.”

Ziaie says, although the device is simple, it involves a large amount of “post-processing.”

Ziaie says a final hurdle to commercializing the device is creating a database that will translate into “actionable information.”