Purdue Method Could Keep Lettuce Safe

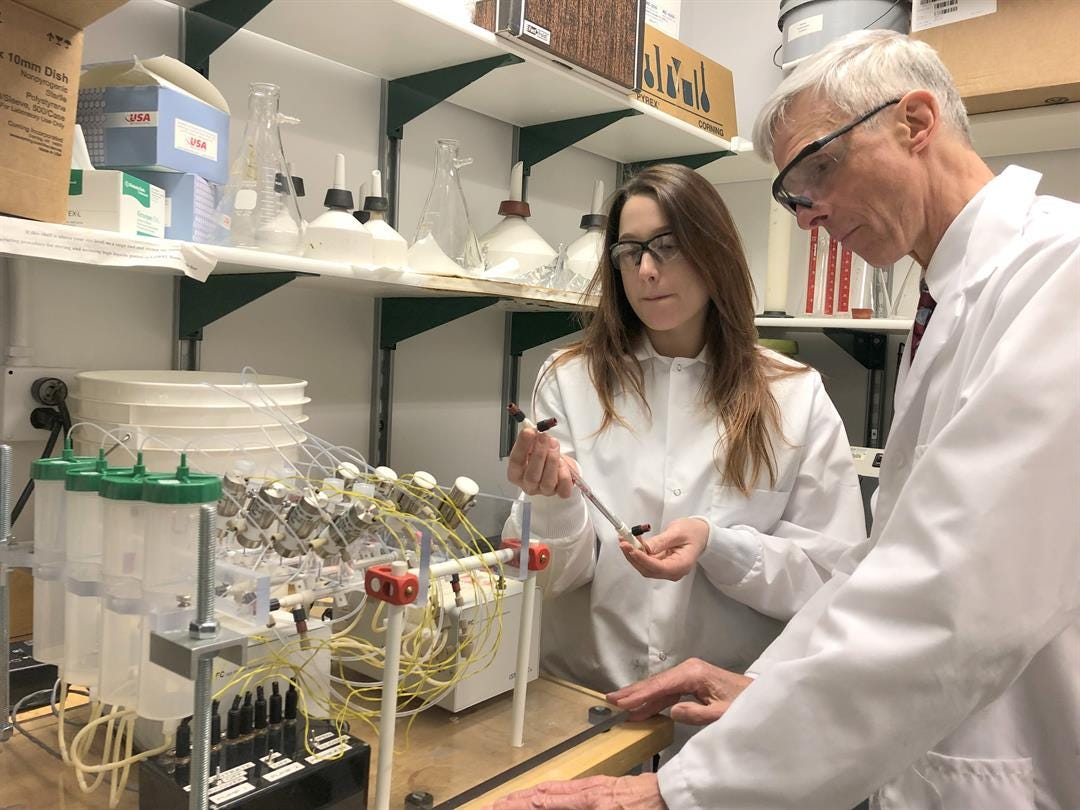

Ladisch and Purdue PhD student Jessica Zuponcic (left) say the instrument could catch elusive bacteria that sneak through current methods.

Ladisch and Purdue PhD student Jessica Zuponcic (left) say the instrument could catch elusive bacteria that sneak through current methods.

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowRomaine has returned to store shelves after a recent E. coli outbreak stopped salads at both grocers and restaurants. Science is partly to blame; the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recalled all romaine as a broad safety measure, because detecting pathogens such as E. coli takes time in the lab—up to three days in some cases. A Purdue University research team believes it can close that window of opportunity for the dangerous microorganisms by finding them faster—within hours.

Experts agree the best strategy for stopping such sweeping recalls is to improve testing methods that clear produce before it reaches the market. While Purdue Distinguished Professor of Agricultural and Biological Engineering Dr. Michael Ladisch says food producers and the FDA are extremely cautious, dangerous microorganisms occasionally sneak through standard screening methods undetected.

“[The FDA] gave us access to their scientists, so we could understand what they’re really looking for and what the problems are in their lab,” says Ladisch, “and we’ve been working on it.”

Conventional methods involve submersing the lettuce in water, which flushes any microorganisms on the lettuce into the water. Those microorganisms in the water—which can include common culprits such as E. coli and salmonella—then must be cultured, or grown to a larger amount, so they can be detected; this process takes one to three days.

The Purdue research team’s method starts the same way: the produce is submersed in water, but there’s no need to wait for the cultures to grow. The water is put through an instrument that uses a microfiltration system; Ladisch likens the incredibly fine “mesh” of the filter to a single hair. The filter catches the bacteria, but the water washes through. What remains in the filter is a much smaller volume in which the bacteria are much more concentrated.

“We concentrate and amplify the number of living organisms; at the same time we concentrate them, we put in what we call media components that enable the cells to grow,” says Ladisch. “They’re doubling in 20 or 30 minutes. It brings the level of microorganisms to a concentration or number where they can be detected.”

The method takes only a handful of hours, compared to culturing, which requires days. The filter also catches and amplifies microorganisms that are difficult to culture, and therefore, wouldn’t grow to detectable levels using conventional strategies.

Realistically, every piece of produce can’t be tested because food is processed in huge volumes, so the FDA and processing facilities use a statistical approach, selecting representative samples to test. In 2015, the Purdue team’s automated filtration system earned the grand prize in the FDA Food Safety Challenge. The FDA is now requesting a method that can test eight samples simultaneously; the team’s current prototype can analyze four.

The team, which includes Purdue Senior Research Scientist Dr. Eduardo Ximenes and Purdue PhD graduate student Jessica Zuponcic, says the method could help prevent foodborne illnesses by reducing the screening time and catching elusive bacteria that sneak through current methods.

Ladisch says the prototype is nearly ready for testing; the team plans to partner with labs that currently monitor food, such as the FDA or the Indiana State Chemist, so the prototype can be used alongside the conventional method.

“We get it to work every time, but now the key is, can someone else?” says Ladisch. “We’re excited about being able to introduce a method that helps move the needle on food safety.”

Ladisch likens current detection methods to finding a needle in a haystack, but the team’s instrument reduces the amount of hay to sift through.

Ladisch believes the team’s instrument could at least triple the analyses a lab could perform in a single shift.