Industry experts defend carbon dioxide storage, discuss report

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Carbon removal was the focus of a two-day, national symposium held at Indiana University Indianapolis, including one controversial state project.

A mile underground, much of Indiana’s rock is porous—and great for safely storing carbon dioxide, industry experts said Tuesday.

Carbon dioxide is captured, then pressurized and cooled. The resulting liquid is injected deep into the earth’s subsurface.

Steve Whittaker, a subsurface executive at Vault 44.01., said his carbon capture and storage (CCS) company was “bullish on Indiana” because its geology comes with “great storage capabilities.”

He spoke on a lengthy 2023 report about ways to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

“We’re going to have to relocate billions of tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to protect … ourselves and future generations from the worst effects of climate change,” said Peter Psarras, a chemical and biomolecular engineering professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “… We really need to look, legitimately, at putting this in the subsurface to make sure that it’s stored durably and safely.”

University of Texas at Austin Professor Susan Hovorka, who’s worked on CCS for 25 years, said she started as a skeptic. But, Hovorka said, “It works.”

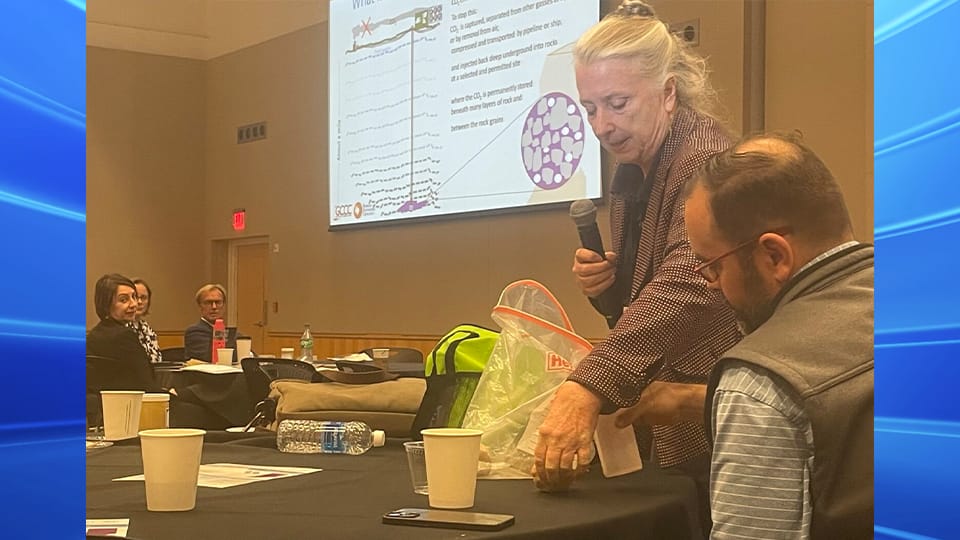

She noted—with visual aids in tow—that suitable rock is porous and absorbs liquids. It’s usually between half a mile and 3 miles underground.

Hovorka sought to address opposition about potential water contamination, earthquakes and explosions.

She told the audience that the industry is highly regulated to protect the water supply—although she said carbon dioxide is “not harmful” to water.

Those same regulations require project operators to prove their injections won’t cause seisms.

To that end, an earlier panelist noted that his company avoids faults, fractures and existing wells. Hugh Caperton II, a development executive at Vault 44.01, said Indiana generally has a “quiet” and “non-complex” subsurface.

Finally, Hovorka said, carbon dioxide doesn’t explode from damaged pipes. It comes out “with energy,” she said, spreading on the ground and mixing with the air. It’s still cold.

“We put on monitors to make sure we’re safe, but it’s not as dangerous as people think,” Hovorka said.

Agribusiness company Archer-Daniels-Midland made headlines this month after discovering a potential underground leak at its Illinois CCS facility, Reuters reported. It paused injections.

Panelists said the facility was unique because it began as a research project and housed multiple functions in the same well.

“Nobody would do those kinds of wells again,” Whittaker said. He said his company would dedicate wells to certain uses, without extra perforations that could lead to leaks.

Indiana is home to four U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Class VI permits for CCS projects.

Wabash Valley Resources External Affairs Vice President Greg Zoeller told the panel that his company has filed two. It plans to produce ammonia for fertilizer at a former gasifier in West Terre Haute and would sequester the resulting carbon dioxide underground.

The company hopes to provide farmers with low-cost fertilizer but has faced local opposition.

Zoeller asked panelists about how they’ve built trust. They emphasized community engagement, and said as more projects progress, there’ll be more concrete examples to point out.

Government Affairs Vice President Pete Rimsans told the Capital Chronicle that the company has met with about 80% of the 200 area organizations it’s identified, and holds weekly meetings with such stakeholders. There are still skeptics, he said, but, “If they don’t engage in the conversation, there’s not much we can do about it.”

The plant is inching closer to reality. It’s expecting to close on a federal loan in the coming months, and begin construction after, according to Rimsans.