Indianapolis takes cue from South Bend on infill housing

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Indianapolis planners are trying to streamline the process for developers to build multi-unit affordable-housing options on vacant city-owned lots.

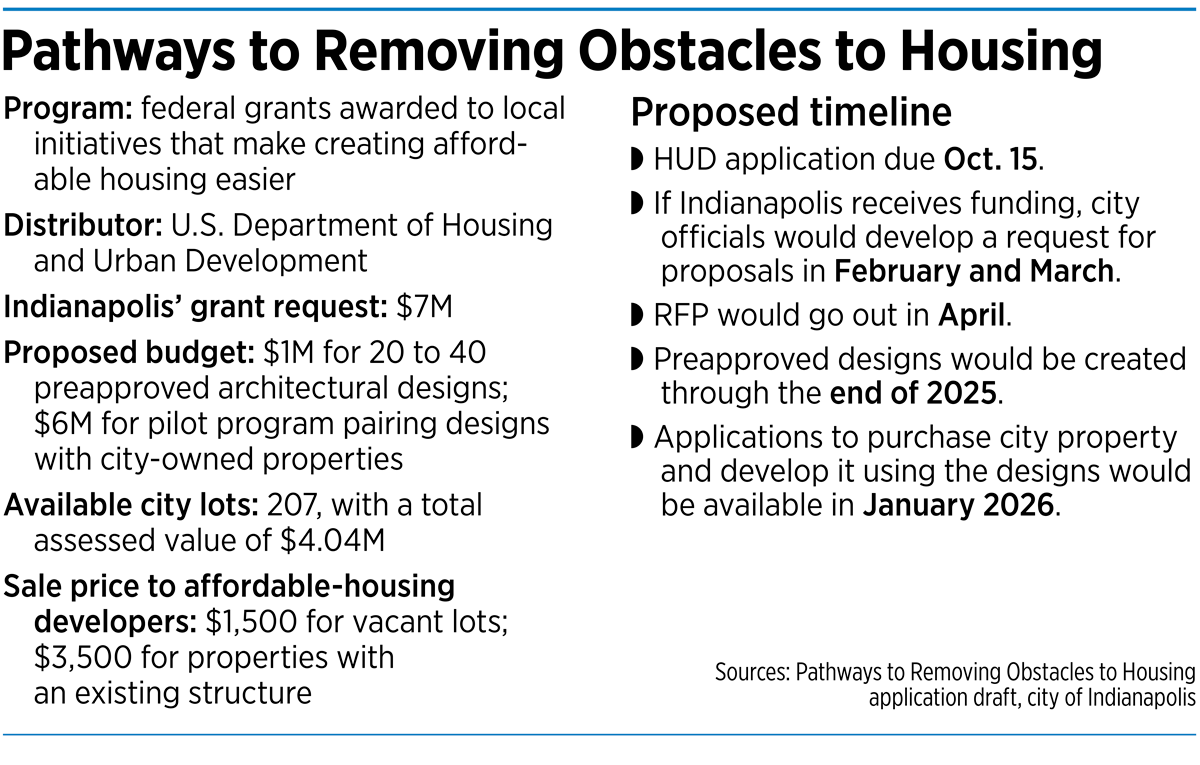

City officials plan to request $7 million in U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development grant funding to create preapproved architectural design catalogs for missing middle housing—like duplexes and triplexes—for developers to build on properties the city already owns.

Think the Sears Roebuck home kits, in which landowners in the early 20th century picked a home design from a glossy catalog and had instructions and building supplies shipped to them.

Planners say the design will make it less expensive, quicker and easier to develop multi-unit infill housing, which is housing built on underused lots in urban areas.

The city’s plan follows in the footsteps of South Bend, which has become a leader in using design catalogs. City officials there say the preapproved designs can save a developer $5,000 to $10,000 per structure.

Housing advocates point to “missing middle housing” as a strategy to increase housing stock because it provides housing options between large apartment complexes and single-family homes.

The federal grant opportunity is Pathways to Removing Obstacles to Housing, or PRO Housing. As outlined in the city of Indianapolis’ draft application, $1 million would go toward creating 20 to 40 preapproved architectural designs while the remaining $6 million would go toward construction.

If the city receives the grant, developers would submit an application outlining their plans to build one of the city’s designs on a city-owned property. Developers whose applications are approved would be awarded a tax subsidy in the form of a grant.

Department of Metropolitan Development spokesman Lucas González said the agency anticipates executing 16 contracts with an average subsidy of $500,000 each, but final funding amounts would be based on criteria like financial need and number of units.

Indianapolis has 207 city-owned plots that DMD has deemed suitable for residential development.

The city’s proposal is due to HUD by Oct. 15.

South Bend’s path

Tim Corcoran, director of planning for South Bend, said he is contacted almost daily by municipalities interested in replicating what South Bend has done. The northern Indiana city has seven preapproved infill housing designs and is in the process of creating two more.

Corcoran has spoken to nearly 50 communities in the United States and Canada.

In South Bend, the architectural plans are publicly available, while Indianapolis would allow only developers who undergo the competitive application process to use its designs.

“The focus of much of what we’re doing here is to create the environment in which new development can happen,” Corcoran told IBJ. And so far, it’s working: Over the next two years, Corcoran said, nearly 100 structures will go up using the city’s designs.

The catalog includes a carriage house, multiple duplexes, a six-plex apartment building and single-family homes. The designs are simple and mostly traditional, Corcoran said, so that “you could probably build one of these in almost any neighborhood in South Bend and feel like it belonged.”

The development community and the city have worked in lockstep, he said, to develop “a better product for the city, but also a smoother process for a developer.”

Generally, Corcoran said, designing a house can cost $5,000 to $10,000—a drop in the bucket when constructing a $300,000 house but a barrier when creating affordable housing.

He said the city is working in other ways also to chip away at housing development obstacles, including a fund that will pay developers up to $20,000 to reconnect an infill house to sewer or water lines.

Lowering barriers

Design expenses, permitting fees, rezoning and variance costs can compound to put a “wet blanket” on small-scale housing developments needed across the city, said Joe Bowling, director of the Englewood Community Development Corp.

“Those are some costs that can cause a small-scale developer to go under and maybe not pursue that next project, if they deem that there’s maybe too many obstacles and too much risk,” Bowling said.

Beth Neville, the city’s administrator of community investments, said architectural designs for federally funded projects have to pass an approval process and rezoning before the city can execute a contract with the developer, so the city cannot reimburse these small-scale developers for architectural costs.

The city’s proposal, she said, is designed to shoulder that burden for grassroots developers and organizations.

Bowling said while he supports the city’s proposal, it won’t be a cure-all.

At a recent Urban Land Institute monthly meeting, Bowling said, panelists were asked, “If you could wave a magic wand and fix one thing in our city and in central Indiana right now, what would it be?” The popular answer, he said, was “permitting.”

Bowling said permitting on a recent Englewood seven-unit town house project took nine months, and the process was took nine months, and the process was neither transparent nor predictable.

The city’s plan “is going to be a tiny, tiny percentage of the development and permitting that happens in our city,” Bowling said. “So you don’t want to kind of say, ‘Well, this will solve that,’ but it will certainly help in terms of making it easier for neighborhood scale infill development from small developers.”

According to the draft application, the city’s review process for new housing construction, including the required design review, Section 106 compliance, and Environmental Release of Funds, takes an average of 200 days. The application says the city wants to reduce that to 100 days.

Neville said certain types of missing-middle developments have a different classification from typical residential properties and trigger a higher level of scrutiny for building code. In taking on the responsibility of creating the designs, she said, the city is also taking on the burden of figuring out how to meet codes with higher-density housing types.

Jeffery Tompkins, an urban design consultant based in Indianapolis, called the grant application “a great first step,” but said a “culture of development around infill” is necessary for the effort to be truly successful. South Bend, for example, has begun offering educational courses and programs for entrepreneurs and entry-level developers on small-scale sites.

Tompkins also said Indianapolis needs to reevaluate its zoning and parking requirements in an effort to promote dense development.

“The city is getting in its own way. It says it wants density, it says it wants more services and amenities, but you have to have people first,” he told IBJ.

While the creation of a catalog of home options might spark concerns of “cookie-cutter” developments, Bowling pointed to his own neighborhood, composed mostly of Sears catalog houses. He said these homes from as far back as 1910 have good attention to detail, are compatible with surrounding development, and have held up for over a century.

The path to starting the city designs will be a long one. Officials will be notified next year if the city is selected to receive funds, and architectural design work would take place through that year.

Applications to purchase city property and develop it using the designs would be available in January 2026.