Externship program places law school students in state’s most lawyer-deprived areas

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Lots of public defenders dream of making a difference for the clients they serve, but few have so stark an opportunity as Chloe Carnes, a recent graduate of the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law.

As one of only a handful of lawyers serving a very rural area, she has the potential to make a very large splash in a very small, very lawyer-deprived pond.

While still in school she spent a summer as a paid extern in the Greene County Public Defender’s Office as part of the Rural Justice Initiative, a program jointly managed by McKinney and the IU Maurer School of Law in Bloomington.

Begun in 2019, it provides paid externships to law students who spend a summer assisting Indiana judges, prosecutors and public defenders in rural counties facing a critical shortage of attorneys.

“I really liked the environment and the smaller office style,” Carnes said of her externship in the Greene County Courthouse in Bloomfield, a community of about 2,300 people 80 miles southwest of Indianapolis.

After graduating from McKinney and passing the bar, she’s now deputy public defender in the tiny Greene County Public Defender’s Office, greatly increasing its ability to assist area citizens.

“I don’t think I would have ended up working here had I not done the program,” Carnes said. “It gives law students a chance to experience something outside of the big cities that the law schools are located in.”

The Rural Justice Initiative, which has so far placed IU law students in 31 Hoosier counties, aims to address a glaring shortage of rural attorneys in Indiana.

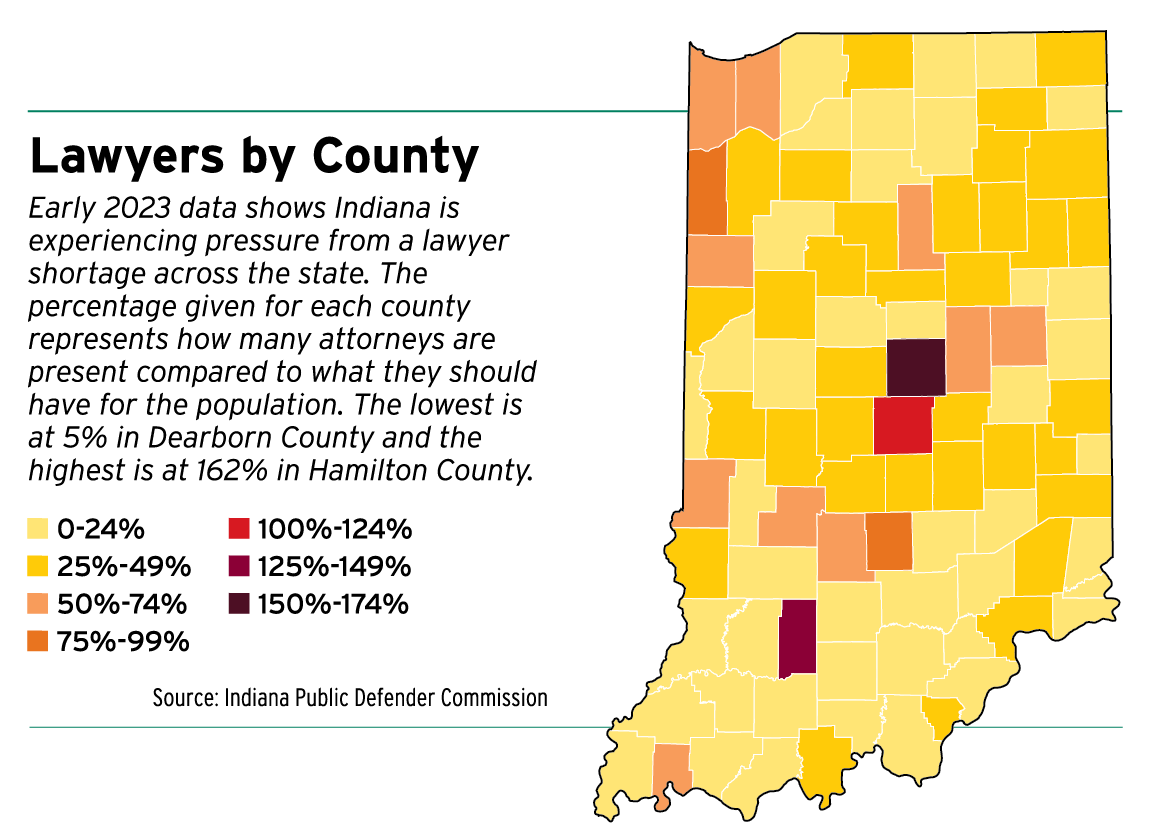

While the American Bar Association’s most recent statistics show that there are roughly 4 lawyers for every 1,000 U.S. residents nationwide, in Indiana it’s an anemic 2.3 per 1,000, placing the state 44th in the nation. More than half the state’s 92 counties are considered legal deserts, defined by the ABA as having less than one lawyer per 1,000 residents.

“In criminal cases there’s a problem with having enough prosecutors and public defenders to be able to make sure the state is represented, the victims of crime are represented and the people charged with the crimes are represented,” said Joel Schumm, director of McKinney’s judicial externship program. “There are some counties that have just a few lawyers, some of whom are semi-retired or on the verge of retirement.”

“This is just one way that our state is trying to deal with this issue, and it’s one way that our law school can contribute to making sure that people have access to legal help,” said Anne Newton McFadden, associate dean for student services at Maurer, who oversees the Rural Justice Initiative at the school.

Indiana’s dearth of lawyers is most glaring in the countryside, where the legal community ofter consists of older attorneys either approaching or past retirement age. The good news is that in areas with populations in the low (and sometimes very low) tens of thousands, even small additions to the attorney population can make a big difference.

“If a program like this results in an area getting just one more attorney, that’s still quite a large increase, percentage-wise,” McFadden said.

She and Schumm say they have no trouble finding students to fill the roughly 8 to 10 slots available each summer at both Maurer and McKinney.

“I would say the program has been extremely popular,” McFadden said. “We have had some judges who have participated every single year, and we usually get at least 20 applicants for eight spots. We try really hard to identify people who want to do this because they really are drawn to these kinds of communities.”

Kayden Mathers, currently a second-year student at Maurer, had a very good reason to spend last summer working in the office of Morgan County Circuit Court Judge Matt Hanson.

“I’m actually from Morgan County, so the issues affecting rural areas, such as access and the lack of lawyers in rural parts of the state, are near and dear to my heart,” Mathers said.

During his tenure he got to see the problems caused by the lawyer shortage—and the efforts to battle it—close up.

“Access to getting a public defender is hard, especially in a rural county,” he said. “We had one public defender appointee who had to Zoom call for all of his meetings.”

Where a student gets placed can depend on many factors, but the most important is typically a practical one—namely, how far they’ll have to drive to get to the office. Often applicants are slotted into the closest opportunity to their hometown, or to the Maurer or McKinney campus, depending on where the applicant will spend the summer.

Another reason for the popularity of the program is the fact that it’s paid. Maurer students receive approximately $4,000 for eight to ten weeks of service. Those in the McKinney program get a similar stipend, but their work time is structured around putting in 20 hours a week, or approximately 200 hours total. The reason for the difference is because while Maurer only sends students to work with judges, McKinney has expanded the program to include public prosecutors and public defenders.

“They started out the same, but McKinney’s has actually evolved somewhat,” McFadden said. “Ours has stayed kind of true to the original iteration of the program.”

Enthusiasm for the effort among county judges has remained steady, with some, including Greene County Circuit Judge Erik Allen, participating every summer since the Rural Justice Initiative started. He thinks the benefits, both to the students and to the judges they serve, have been bountiful.

“We do not have the resources to hire interns or law clerks, so we’ve been able to have the assistance of somebody doing research for us, drafting orders or other documents we need, or doing administrative stuff we’ve been trying to find the time to do,” Allen said.

On the other side of the coin, his interns can hone their research and writing skills in the real world, watch a wide variety of hearings and see judges and attorneys at work.

“I think it’s a good experience for them to see what areas of law might or might not interest them,” Allen said.

That was certainly the case for second-year Maurer law student George Admire, who last summer worked with Shelby County Superior Court Judge David Riggins. A resident of Johnson County, where his father practices law, Admire made the daily drive from the next county over to work with Riggins, who made a point of showing him the practical side of courtroom work.

“In law school you learn how to think like a lawyer, but you don’t really know how to talk to a client, how to talk with other lawyers, and how to handle other real-world interactions,” Admire said. “But I was in the courtroom every day, watching these relationships unfold.”

Since returning to school, he’s recommended the Rural Justice Initiative to three or four first-year Maurer students.

“It’s an experience you can apply wherever you go in the profession,” Admire said. “I think that no matter what you do in law, whether you’re in the courtroom or not, experiencing this sort of practical work is foundational for everything else you will do as a lawyer.”

But will the program solve Indiana’s lawyer shortage? Probably not by itself, though Allen thinks it could make a major dent.

“Even if it doesn’t end up sending dozens and dozens of lawyers permanently into rural areas, just a few can often help immensely,” he said. “One or two lawyers can make all the difference in providing enough legal services in rural areas.”