Boilermakers Build Pod to Blast Through Hyperloop

The students' pod design was among 30 selected to advance to the next SpaceX competition.

The students' pod design was among 30 selected to advance to the next SpaceX competition.

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowImagine buckling into a pod and being fired through a tube at 700 mph to your destination. Sound far- fetched? A group Purdue University students doesn’t think so; they’re devoting their undergraduate years to help make this scenario entirely possible—and capturing awards for their ingenuity. Called the Hyperloop, the concept is the brainchild of Elon Musk, the same mind behind Tesla and SpaceX. The idea is moving closer to reality: a building permit has been submitted in California to start tube construction—and the team of Purdue students wants to design the vehicle for the brave souls who someday could travel the tube.

The building permit—filed by the company developing Musk’s idea—will clear the way for the first 5-mile stretch of the Hyperloop in Central California.

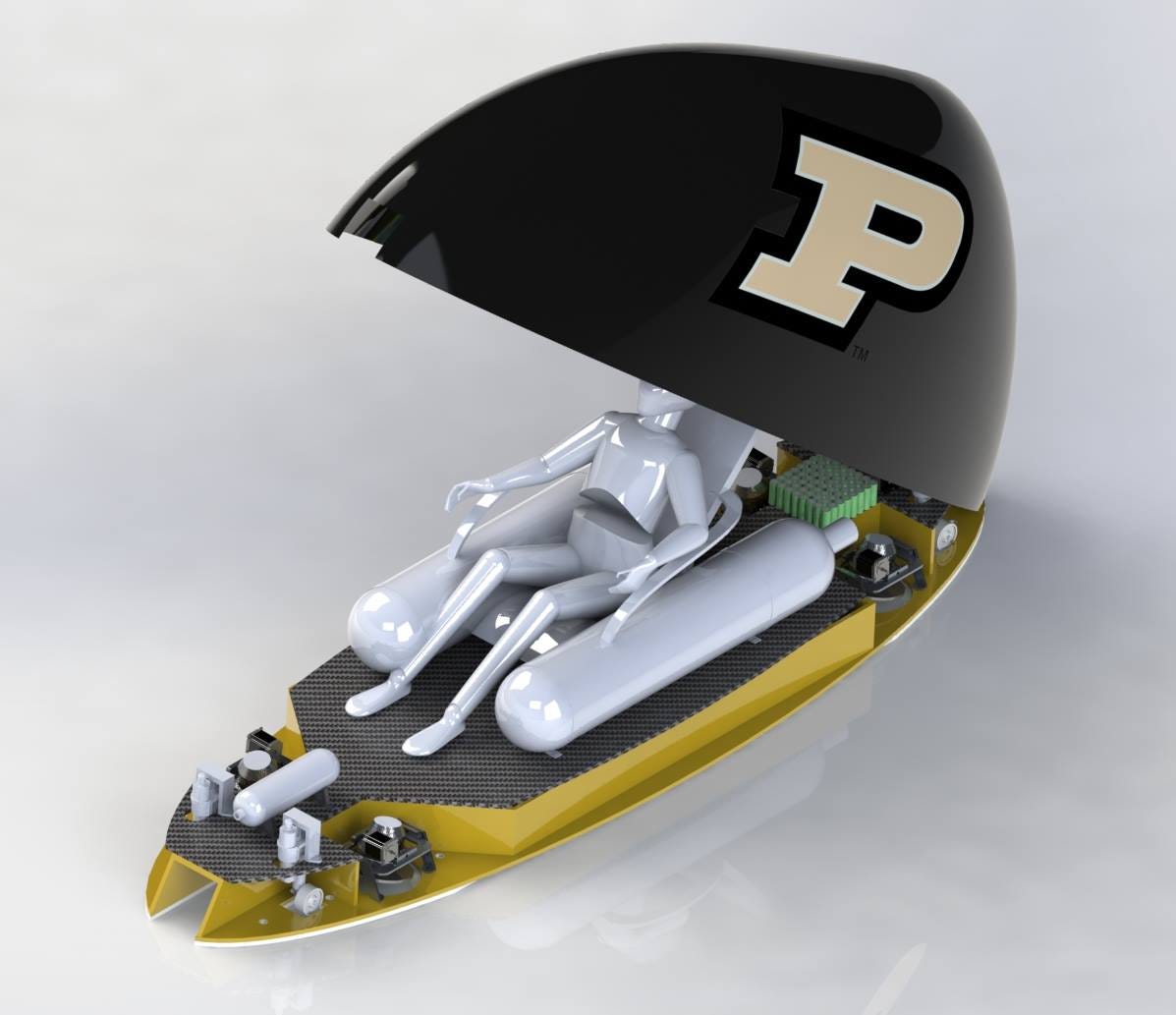

“The basic concept is to make a tube between two cities, suck out a lot of the air—so it’s a very low pressure tube—then launch a pod with people or cargo in it to be transported at a very rapid speed,” says Paul Witsberger, a Purdue senior studying Aeronautics and Astronautics Engineering and team captain of the Purdue Hyperloop team.

Formed less than a year ago, the team is about 50 students strong—all undergraduates from eight university departments. Purdue is among many universities throughout the country working to design the vehicles, or “pods,” that will travel inside the tube. In addition to human transportation, the Hyperloop is being hailed as a futuristic method to move cargo.

“The energy cost per trip for the Hyperloop between two destinations is lower than planes, trucks, trains—it’s economically one of the most viable transportation concepts,” says Witsberger. “This would be able to greatly reduce cost per good, or at least alleviate the current demand on our roads right now.”

In January, the students took their design to a national SpaceX Hyperloop pod design competition, where they competed with 80 other university teams; Purdue was among 30 selected to advance to the next phase, where teams will take their designs from paper to prototype.

No physical “track” exists inside the tube, so teams must figure out how to levitate and propel their pods. The design Purdue Hyperloop took to the January competition involved air bearings, which Witsberger likens to an air hockey table: “but rather than blowing air up, the pod would blow air down and float on that cushion of air.”

But after determining the heavy compressed air tanks would add drag, the team has now moved to a magnetic system.

“If you move permanent magnets on the bottom of the pod fast enough over the aluminum [surface of the tube], you can produce magnetic lift,” says Witsberger. “So just by moving fast enough over the track, we’ll be able to make our own lift; we’ll be floating as we’re traveling through the tube.”

Taking advantage of high-tech carbon fiber manufacturing facilities on campus, the team will soon begin building its pod for the next competition in August. SpaceX is building a one-mile, half-scale tube in California for the competition, where teams will launch and test their prototype pods.

In addition to tackling the technical side of the project, the team must also raise money, find sponsorships and earn donations to build the pod and attend competitions. The team’s faculty advisor says the project has become somewhat entrepreneurial and evolved much like a technology startup.

“It’s beyond engineering,” says Purdue College of Aeronautics and Astronautics Associate Professor Dr. Alina Alexeenko. “I’ve seen them become very confident, professional engineers, solving a very challenging design problem and all of the issues that come with doing a real-world engineering system design from scratch. It’s not that they’re trying to improve anything—they’re trying to invent something that has not been done before.”

The team says it’s on the doorstep of partnering with Indiana-based composite manufacturers to build the pod, and Alexeenko is hopeful the team could collaborate with Indianapolis-based INDYCAR in the future, because racecars’ high-speed braking system is similar to what the pod will need.

While Witsberger admits some people think he’s crazy for dedicating such long hours to what—for now—is just a big idea, “I think the Hyperloop will become a reality in the future,” he says, “and I’m enjoying every moment of it.”

Witsberger says all of the systems on the pod—and their designers—have to coordinate with each other.

Witsberger says the project has been a crash course in solving a “real-world” engineering problem.

While a group of Purdue professors may start conducting research focused on the Hyperloop, Alexeenko says students are currently leading the charge.