Techshot Builds Blood Vessels for Wounded Warriors

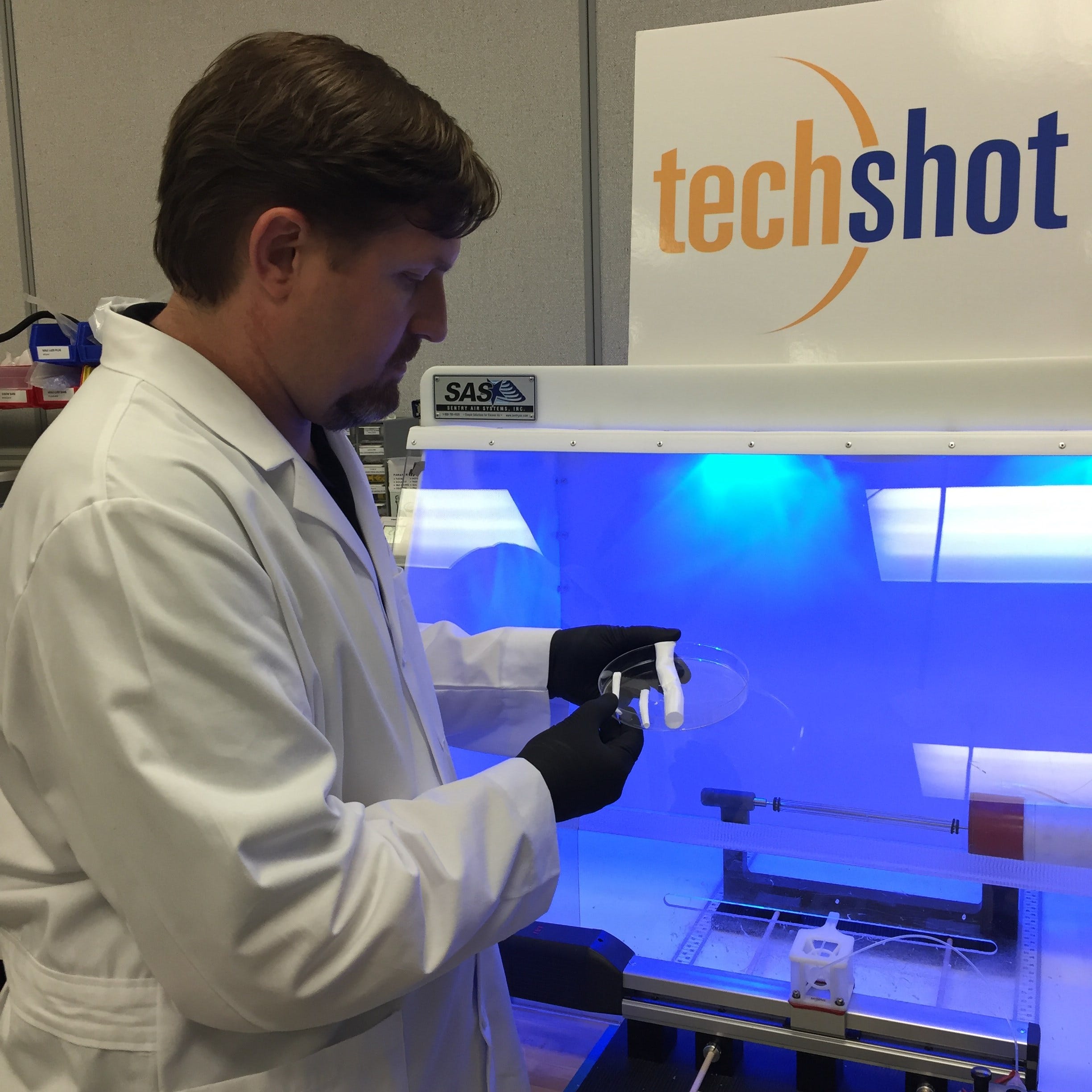

Boland invented the tubular scaffold.

Boland invented the tubular scaffold.

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe widespread use of explosives on modern day battlefields is leading to an alarming number of amputations among soldiers, but Greenville-based Techshot is fighting back. The technology development company has invented a process that creates major human blood vessels from a patient’s own stem cells; the decision to amputate an arm or leg often hinges on the availability of such vessels. Perhaps even more incredible, the project is a stepping stone to 3D printing human tissue—think of an entire heart—from a patient’s own cells.

“3D printed human tissue is all about getting blood in and out of solid tissue—that’s going to be the hallmark of whoever succeeds at 3D tissue printing,” says Techshot Chief Scientist Dr. Eugene Boland. “If we have a successful vascular graft, then we’ll put a flag in the ground saying we know how to get blood flow in and out of tissue.”

Funded by more than $1 million from the Pentagon’s Defense Health Program, the project centers on Techshot’s process of creating vascular grafts to help military personnel avoid amputations. Blast injuries often destroy major vessels needed to repair a wounded arm or leg, but Techshot has developed a method to create vascular grafts—basically small tubes—that can replace injured vessels. The graft acts as a scaffold for healthy tissue to grow on, and is then absorbed by the body.

The tubular scaffold is made through a process called electrospinning, which is a way of producing extremely fine fibers.

“Think of how cotton candy is produced, but you’re directing these fibers around a target to form a tube. Eventually they build up and form this tube,” says Boland. “It looks like a solid tube, but it’s really created with fibers that are about 50 to 200 times smaller than a human hair.”

Stem cells taken from the patient’s fat are then cultured, or grown, and printed onto the tubular graft; the fibers are so fine that individual cells are able to interact and heal within the fibers and, eventually, grow a healthy vessel in place of the graft, which gradually disintegrates.

Boland says the grafts will be pre-manufactured and have a shelf life of at least 6 months. When a soldier is injured, the cells can be applied to the graft and implanted into the patient—all within a one to two-hour time period in the operating room.

Techshot says its process is a drastic improvement on the conventional treatment of blast injuries, which typically involves bypass grafts; an uninjured major vessel in the arm or leg is harvested to create a graft at the injury site—but often explosives injure multiple limbs.

“Whether or not a patient has a spare vessel available should not be the deciding factor in whether they lose their injured limb or keep it,” says Boland. “Bypass [grafts] do create deficits in the area where the vessel was taken from; you really don’t have any ‘spare’ vessels in your body. They’re all serving a purpose.”

The vessel project works hand-in-hand with the company’s effort to create a 3D human tissue printer. Techshot says the ability to make vessels is a critical prerequisite for 3D printing tissue or complex organs, because the new tissue must be able to vascularize. Company leaders says small vessels essentially grow on their own, but major vessels need to be manufactured.

While printing human organs may seem like science fiction, Techshot says it fits right into its wheelhouse, which includes decades of creating scientific hardware for space flight. Amazingly, experts believe tissue printing has the most promise in space.

“Gravity really sucks for 3D tissue printing. We think where 3D tissue printing is really going to succeed is in space, because everything you do to try to support 3D tissue printing on the ground kills cells,” says Boland. “If we can get rid of the whole gravity factor, I think we can make some really cool tissues in space.”

But first, the company will focus on its earthly pursuit of helping wounded military men and women. Expecting to begin military clinical trials within two years, followed by civilian applications soon after, Techshot’s battle plan for fighting amputations is clearly drawn.

Despite its high-tech nature, Boland says Techshot’s method will be applicable on the frontline.

Boland describes the challenges that lie ahead for its vascular graft technology.