‘Real loss from COVID is in front of us’: Study finds lack of learning recovery after pandemic

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

The learning loss students experienced during the pandemic is unlike any other similarly widespread tragic events in history, including World War II, the Great Depression and the Spanish Flu epidemic, according to one Indiana researcher.

A recent Ball State University study illustrates how the pandemic triggered historic learning loss in Indiana schools as shown by the dramatic drop in passing state test scores in reading and math in multiple grade levels.

What surprised researchers was the stalled recovery, which could likely have severe ramifications for affected students’ future academic success, careers and wages. Without an adequate recovery, Michael Hicks, director of Ball State’s Center for Business and Economic Research, said tens of thousands of kids in an eight-year span could leave high school having never recovered from the pandemic.

“The real loss from COVID is in front of us,” he said.

Learning loss stemming from the pandemic is a nationwide issue. However, Indiana has long battled to improve their literacy rates specifically as well as overall state test scores.

What researchers found

The most recent study spanned two academic testing years from 2021 to 2023. A prior study focused on one test taken from 2019 to 2021; the 2020 test was scratched. Researchers wanted to continue to watch the effect on educational attainment and what contributed to more critical learning drops.

Data stems from the state-issued test ILEARN, which is required for students in third through eighth grades and predominantly covers math and reading. ILEARN replaced ISTEP in 2019.

Though test scores don’t tell students’ entire educational story, Hicks said they are strong predictors of learning loss when data is looked at from a school-to-school level, rather than individual student scores. These tests are specifically looking to see what a student has learned over the past year, he said, and what was found is that the rate of students not retaining or learning what is expected is higher than pre-pandemic levels.

While scores have modestly rebounded from the shock of the first year, Hicks said they’ve plateaued.

“Three years after COVID, that learning loss is has been big enough and persistent enough that it seems unlikely that schools are going to be able to bridge that pass rate for most students who went through COVID,” he said.

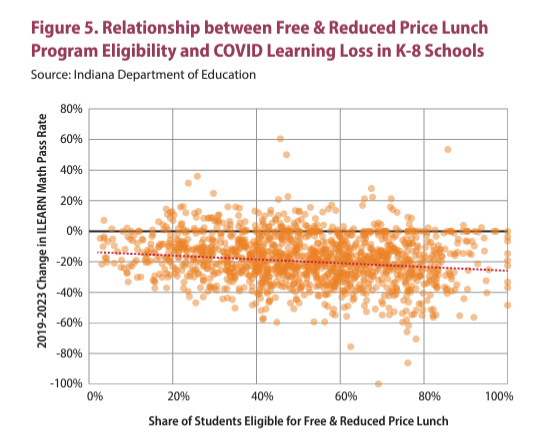

The study’s goal was to find reasons contributing to learning loss, and to little surprise, poverty is the primary factor determining the severity of learning loss. That finding is consistent across grade levels and subjects.

“Poverty is driving this,” Hicks said. “There’s not really any other factors that are alone playing a role.”

Demographics like race and ethnicity, which the state hypothesized as correlated, were found not to have a direct impact in the study.

Another factor Hicks said wasn’t significantly instrumental to the loss was online learning. Indiana was a “perfect experiment,” he said, because schools across the state took different approaches to addressing COVID-19 with everything from fully online to entirely in-person. The data didn’t show this was an overwhelming factor, he said, and there are schools with operational differences that were comparable. Rather, he said it could be a collection of issues weighing on students at the time, including the deaths of family members due to COVID, integration of technology in education and other disruptions.

Hicks talks how he and other researchers were surprised at the lack of recovery in the data from their first study to the second.

High-performing schools had the largest absolute learning loss from the onset of the pandemic. However, those schools were found to likely have less learning loss in the new data, signaling a stronger recovery than their lower-performing counterparts.

That trend and others pushed researchers to the conclusion that strongly suggests that post-COVID learning loss and recovery are tied to what’s happening in classrooms.

Future studies will continue to show the recovery and progression of the COVID shock to the education system. Over time, Hicks said this data will also show the efficacy of how material is taught with the rise of more digital learning and if those strategies are good substitutes for traditional in-person instruction.

Study: “This is a public policy problem of the first order”

Education is the single largest economic development issue in Indiana, Hicks said. So with test scores signaling such a dramatic learning loss as well as education accounting for half the state budget, he said lawmakers are prompted to act.

The study repeatedly says policy is needed to remedy learning loss and continuing disparities. It also says such research can be a guide to funnel resources and money toward the school districts that need it.

The legislature has taken these issues seriously and paid close attention, Hicks said. However, he noted they often approach solving these problems without research.

“So we’re going into this debate blind,” he said. “It’s the right debate to have, but having it without having done the fundamental research about the efficacy of the different options is just not responsible.”

Some of the solutions are focusing on individual student success rather than how public education is funded and supported, he said, pointing critically to legislation potentially holding back third graders who don’t pass the reading test.

“It’s as if we’re playing Jenga with the whole system,” Hicks said. “Looking at one block and tweaking that and poking that and wondering if that’s going to be a miracle cure—there just are not miracle cures.”

Hicks looks back on Indiana educational policy and continuing issues the state is seeing.

The biggest issue is resources, he said, talking about adding supplementary tools, improving teacher training and addressing learning gaps caused by shifting norms—like the decrease in the number of stay-at-home moms who can work with their children on homework.

Resources include providing attention to students who are struggling or need different tactics to learn, Hicks said. That doesn’t just mean people who are dedicated to fixing the issue, he said, but people who understand how to offer children different avenues to educational success.

“In an environment where we offer a lot of choice, we don’t offer a lot of resources to make that choice really affect outcomes,” he said. “That’s the challenge.”