New UAW president, a Kokomo native, pushing hard, raising expectations

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

He grew up in a working-class family in this blue-collar town.

His father was a police officer, rising to police chief. His mother was a nurse. Two of his grandparents were members of the United Auto Workers at General Motors. His other grandfather started at Chrysler in 1937, the year the workers joined the union after a sit-down strike.

Now, Shawn Fain, a union blueblood who began his career on a factory floor at Chrysler’s Kokomo Casting Plant (now part of Netherlands-based Stellantis NV), is leading a high-stakes battle as new president of the UAW.

In just a few months, he has gone from obscurity to one of the most visible leaders in America, pulling, cajoling, demanding that his workers get more concessions from the Big Three automakers after two decades of givebacks.

He coaxed his membership this summer into authorizing a union strike against GM, Ford and Stellantis. And when the automakers didn’t meet the union’s demands by the Sept. 15 deadline, the UAW began striking large plants.

It’s a huge movement that has gained the daily attention of major media. Together, the three car companies employ 145,000 UAW members, including more than 13,000 in Indiana, and make about half of the 15 million vehicles assembled in the United States each year. This is the first time the UAW has struck all the Big Three automakers at once. As of midweek, no Indiana plants had been targeted.

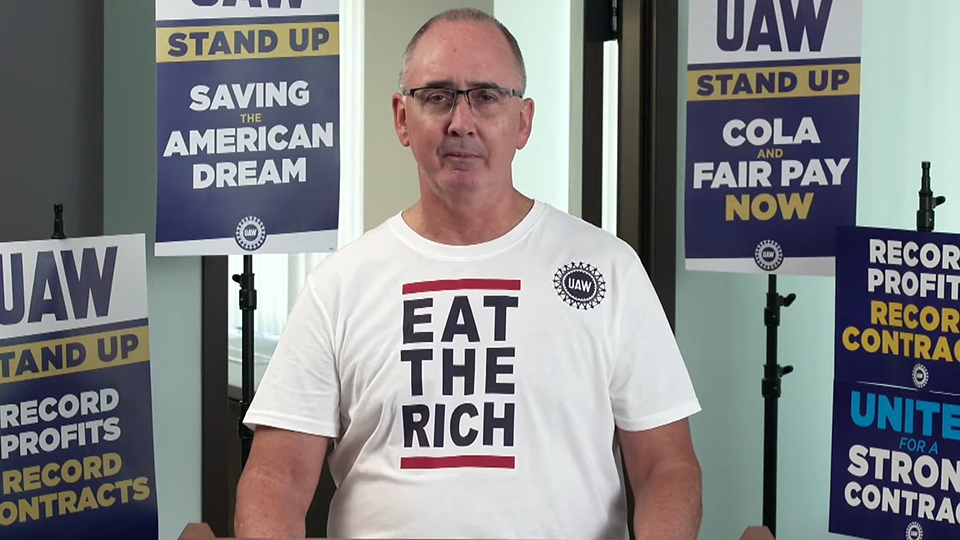

The man leading the charge hardly looks like an agitator. With his receding hairline, glasses and slight paunch, the 54-year-old Fain seems more like a small-town accountant than a firebrand union leader.

But when he talks about trying to get a better contract, he strikes a defiant, almost militant tone.

“The money is there. The cause is righteous,” Fain told union members during a Facebook livestream last month as the union readied to strike. “The world is watching, and the UAW is ready to stand up. This is our defining moment.”

His words have aroused battle cries from many of his members, who say they are behind him and think it’s time to get a better deal from the auto industry. Some civic leaders said Fain has built trust quickly with members since winning his razor-thin victory as UAW president in March.

“He’s very serious. He’s very sincere,” said former Kokomo Mayor Greg Goodnight, who worked at Haynes International and was president of Steelworkers Local 2958 when Fain was president of UAW Local 1166. “And he is a good union activist and very well-spoken. And he is very committed to his members. And they appreciate that.”

Harley Shaiken, a professor at the University of California Berkeley who has followed the UAW for more than three decades, said Fain’s upbringing has played a huge role in his outlook.

“I think, clearly, the years he spent as an electrician in a Chrysler foundry in Kokomo … shaped important parts of his worldview,” Shaiken said. “He knows what it means to be in a factory. He knows what a worker’s life is like.”

‘Heated rhetoric’

But Fain’s rhetoric and demands have also prompted harsh criticism from leaders of the Detroit automakers, who say they have offered fair contracts but the union is seeking too much.

The union has asked for a wage increase of up to 40% over four years, along with full pay for 32-hour workweeks, better retirement pensions and improved health care. Fain has pointed out that in the first six months of this year, the Big Three made a combined $21 billion in profits.

That’s on top of about $250 billion in North American profits they made over the past decade, according to the UAW.

“Record profits equal record contracts,” Fain told members. The UAW did not make him available to IBJ for comment.

Mary Barra, CEO of GM—the largest U.S. automaker, whose brands include Chevrolet, Buick, Cadillac and GMC—said her negotiators worked “days, nights and weekends” since receiving the UAW demands. The last GM offer included 20% wage increases over four years, no changes to health care premiums, wage steps cut in half to four years, and other features.

“It addresses what you’ve told us is most important to you, in spite of the heated rhetoric from UAW leadership,” she wrote last month, a day before the union walked off the job at GM’s huge Wentzville Assembly plant near St. Louis.

The same day, union members also walked off the job at Ford’s Michigan Assembly Plant near Detroit and Stellantis’ Jeep assembly plant in Toledo, Ohio. More than 12,000 UAW members work at those three assembly plants.

Last week, the UAW expanded its strike to 38 GM and Stellantis NV parts distribution centers in 20 states, representing an additional 5,600 workers. As of midweek, no plants in Indiana had been struck. But auto-parts maker Dana has laid off about 240 workers in Fort Wayne, and GM has laid off 34 workers at a metal plant in Marion amid halted operations at plants elsewhere.

On Sept. 26, Fain and his union picked up another big supporter. President Joe Biden made an appearance at a UAW picket line at a GM parts warehouse in suburban Detroit.

“You deserve a hell of a lot more,” Biden said through a bullhorn while wearing a union baseball cap. Several political analysts said Biden was the first modern president to visit a picket line.

“No deal, no wheels!” workers chanted as Biden arrived, according to televised reports. “No pay, no parts!”

Biden was joined by Fain, who rode with him in the presidential limousine to the picket line.

“This is a historic moment,” Fain said.

Inspiring past

Inside a trophy case in the lobby of UAW Local 685 in Kokomo is a small, yellowing paper booklet no bigger than a wallet.

It’s a copy of the union’s first retirement plan, reached in 1949, just 13 years after the UAW was established in Detroit as part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations to bargain on behalf of hourly auto workers.

The document is something of a laurel for the union, a reminder of its first major pension agreement.

“We won’t sign a contract at Ford in ’49 that does not include a pension plan,” Walter Reuther, the legendary UAW president, had told 5,000 Ford workers in Detroit. When Reuther called for a strike vote, hourly workers authorized it by a huge majority.

A few months later, the UAW won a $100-a-month pension, its first ever.

Today, Fain is telling union members they have to show the big automakers they are willing to stand up for their rights on pensions, health care and other benefits.

The UAW gave concessions right before the 2008 financial crisis to help the automakers recover. Some, like GM, had fallen into bankruptcy and were rescued with a government bailout.

These days, Fain sometimes sounds like U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Massachusetts, who is known for knocking the ultra-wealthy.

“The billionaire class is scared, and the Big Three is scared,” Fain said in a video posted on the UAW website last month. “They want to make you think you don’t deserve your fair share.”

Down the hall from the trophy case, in a windowless office tucked in a small corridor, Denny Butler, vice president of Local 685, said he voted for Fain as national president and supports the strike, even though his local is not among those on strike.

He is helping coordinate the local’s “red shirt days,” where union members walk in a practice picket line on Sundays near the Stellantis casting plant.

“It’s inviting the entire community to show what we are,” Butler said. “We’re just normal people. We are the middle class. We shop at Kroger. We shop at Meijer. We spend money at Kohl’s.”

He said the event is meant as a reminder to Kokomo that several thousand workers with union wages help support the town.

“I think the perception of some people is, we’re looking for something we don’t deserve,” Butler said. “That’s just not the case.”

Fain’s stomping grounds

About 4 miles north, in the union hall of the other Kokomo UAW chapter, Local 1166, bulletin boards in the lobby tell of strikes over the years.

The clips range from the 1962 walkout that idled almost 3,000 workers at a Chrysler die-cast plant and a Continental steel mill, to a brief strike last fall at the Stellantis casting plant. The latter strike grew out of a disagreement over better working conditions, including clean uniforms and repairs to the factory’s HVAC system. The two sides reached an agreement within two days.

“We thank everyone for the solidarity you have shown,” the local bargaining committee told members in a letter after reaching the tentative agreement.

This is Fain’s local, the one he joined in 1994 as an electrician at the Chrysler casting plant. He was elected to five terms as a skilled trades committeeman and plant shop chairman. Today, Local 1166 represents some 1,000 Stellantis employees in Kokomo.

The local leadership says many of the members know Fain and are backing him up. “We’re supporting him completely,” said Doug Harnish, the local’s vice president.

But whether the Kokomo union members are truly prepared for a strike is unclear. The presidents of the two locals did not return repeated phone calls to IBJ to discuss their plans for a potential strike. And only about 300 people turned out for Local 685’s “red shirt day” two weeks ago—a small fraction of the local’s 6,000 members.

Fain’s relationship with the national union hasn’t always been smooth. In 2007, when he was a committeeperson at Local 1166, he refused to go along with the recommendation of UAW’s national leaders to accept deep concessions from Chrysler, which was newly divested from German parent Daimler-Benz AG. (GM and Ford were also asking for concessions.)

Fain wasn’t having it. “Two-tier wages have no place in this union,” he declared. And in a letter to the UAW, he wrote, “You might as well get a gun and shoot yourself in the head.”

The two Kokomo locals overwhelmingly rejected a tentative contract with Chrysler. Yet the UAW ratified the contract in a close national vote, with 56% of production workers, 51% of skilled trade workers, 94% of office and clerical workers, and 79% of engineers represented by the UAW voting to take the deal.

“With that defiant step, Fain declared his independence from the political group—known as the Administration Caucus—that had run the UAW for six decades,” Politico reported last month. “And the move also set him up for a higher position—for years in staff jobs at UAW headquarters in Detroit, then later to be catapulted into the union’s presidency.”

Making his move

Fain left Kokomo about a decade ago to take a job as international representative at “Solidarity House,” the nickname for the Detroit headquarters building of the UAW. In that role, his job was to assist in a wide range of areas, including contract bargaining, administration and enforcement, organizing, civic engagement, health and safety, and civil and human rights.

“He wasn’t particularly high on anyone’s radar at this point,” Shaiken said. “He was in three or four national negotiations, but he never led these negotiations and did not have a particularly high profile.”

But what propelled Fain into the forefront was a series of events, including a corruption probe in 2020 by the U.S. Justice Department against UAW leadership and several Fiat Chrysler executives.

The probe resulted in the convictions of 12 union officials and three Fiat Chrysler executives on charges of racketeering, embezzlement and tax evasion. Several people, including two former UAW presidents, were sentenced to prison.

That resulted in a widespread move to reform the union. By a nearly two-thirds majority, rank-and-file union members voted to switch to direct election of top officials, replacing the traditional system where union officers were chosen by delegates at a national convention.

And Fain decided it was time to make a move, even though he was not a household name throughout the union.

“His chances of victory were very slim at the time he sought to do it,” Shaiken said. “But he did it.”

The reason the chances seemed so thin was because no one had defeated the old guard since the 1940s. The reform wing of the union had not won the top leadership positions in decades.

Fain adopted a confrontational strategy with the Big Three from the start of his campaign, saying it was time to be tougher with the automakers after years of givebacks.

“This is our shot for true reform of the UAW and putting the power and control of our union back in the hands of the membership by electing leaders who will be held accountable by the membership,” Fain told Reuters last year.

In the March election this year, Fain squeaked out a victory, defeating the incumbent, Ray Curry, a former assembly line worker who was appointed president in 2021. Curry was not implicated in the corruption scandal that sent some of his colleagues to prison.

But Fain made the case that Curry was not enough of a break with previous presidents linked to wrongdoing. Fain won the presidency by fewer than 500 votes, or about 1 percentage point.

Shaiken said UAW members, beaten down by years of givebacks, locked into Fain’s tough talk and decided to give him a chance.

“What he was saying was very sharp at times, some belligerent rhetoric, but it really resonated with workers on the line and in the factories,” Shaiken said. “It wasn’t that he was agitating them. He was reflecting real sentiments, anger and frustration in the factories.”

Once elected, Fain did not let up on his wartime rhetoric. In his inaugural address to the membership, he made it clear what he viewed as the stakes.

“We’re here to come together to ready ourselves for the war against our one and only true enemy,” he said, “multibillion-dollar corporations and employers that refuse to give our members their fair share.”

Key moment

Fain’s election, and his pulling the union into a national strike, is taking place at a historic moment in the auto industry.

Automakers are shifting quickly to electric vehicles, a move Shaiken calls the biggest transition since Henry Ford introduced the moving assembly line in 1913.

The union is working to organize several battery plants that the three Detroit automakers have built or are building with partners. Stellantis, which was formed through the merger of Fiat Chrysler and the French automaker Peugeot, announced plans last year to build a battery plant in Indiana.

Stellantis said in May 2022 it signed an agreement with renewable-battery company Samsung SDI to build a $2.5 billion electric-vehicle battery plant in Kokomo, which is expected to open in 2025 and create up to 1,400 jobs.

Two months later, Stellantis said it would build a second U.S. electric vehicle battery factory in a joint venture with Samsung to open in early 2027. It didn’t disclose the location.

Stellantis is planning for half its U.S. passenger-car and light-truck sales to be battery electric by 2030. The company wants 100% of its sales in Europe to be electric in the same time frame.

Throughout his recent union rise, Fain’s public demeanor has been mostly serious. On his videos, which are archived on YouTube, he speaks in a strong voice, looking directly at the camera, making his case for why he is pushing the union to get tough.

He has said he won’t shake hands with the automakers’ CEOs until a deal is reached—a break from the traditional ceremonial handshaking on the first day of negotiations.

“The members come first,” Fain said in a statement. “I’ll shake hands with the CEOs when they come to the table with a deal that reflects the needs of the workers who make this industry run.”

He dresses neatly, often in UAW golf shirts, and speaks in a loud, steady voice, sometimes quoting Scripture, other times quoting Martin Luther King Jr.

In June, he attended the MLK 60th Commemorative Freedom Walk with the Detroit branch of the NAACP and quoted a passage from the book of Ecclesiastes, which he called his favorite: “Two are better than one, because they have a good reward for their labor. For if they fall, the one will lift up his fellow.”

He still carries in his pocket one of his grandfather’s Chrysler pay stubs from 1940, a reminder of Fain’s family ties with the union.

But for all his serious manner and big goals, will Fain be successful? Can his union, with a mixed history of success and corruption, get what it wants from huge automakers?

“I am optimistic the UAW will win significant gains in this contract,” said Art Wheaton, director of labor studies at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations. “It is helpful this time to pit all three companies against each other to set the pattern.”

But he added, it remains to be seen if Fain can get a deal ratified after dramatically raising expectations.

And Goodnight, the former Kokomo mayor, said he has a feeling that Fain is walking carefully, despite his tough words.

“Knowing him, he’s thought this out,” he said. “He’s probably always contemplating and considering what his next two or three moves would be. He’s not someone to overreact.”