Elkhart officials, Notre Dame partner to envision future for urban renewal

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Sheneen Haley was practically jumping out of her seat as urban planners described their vision earlier this month for her neighborhood in Elkhart’s Benham area.

She’s lived there for more than three decades, and her grandparents have been there even longer. When her family first moved to the historically Black neighborhood in the 1960s, their street was a thriving, close-knit community. But, Haley said, she could see the change when she moved in with her grandmother in 1991. Shoddy renovation work and failed promises for revival from past city officials left the neighborhood with empty storefronts and vacant lots.

Now, as present day officials move to revitalize Elkhart’s downtown, demand for housing in the Benham neighborhood, just blocks south of the city center, is growing.

City officials see potential for the long-neglected area to become Elkhart’s next up-and-coming hot spot. But, to do that, Elkhart leaders will need to wade through years of restrictive zoning policies and set new standards as developers court residents to purchase their homes.

With the help of the University of Notre Dame’s School of Architecture, city officials are making both short- and long-term plans, and hoping to tap into newly available state funds for housing infrastructure. That is welcome news to Benham-area residents like Haley, who’s seen little investment in her neighborhood over the years and wondered whether it was time for a move.

“What’s going to keep us here?” Haley asked. “I will have at least 40 years of work experience, 40 years of knowledge of working in this community. I can easily take that somewhere else. What’s going to make me want to stay here?”

Creating a plan

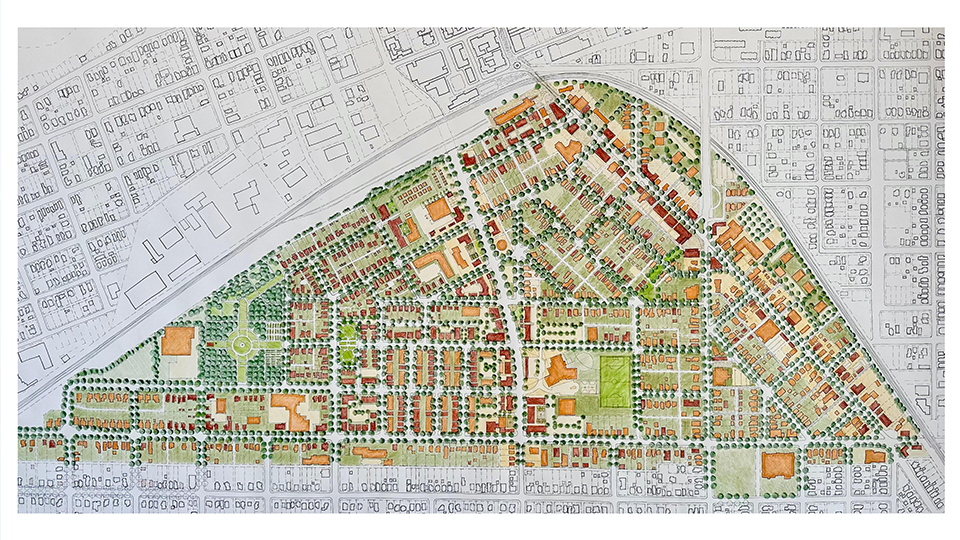

In mid-August, dozens of architects, civil engineers and experts in urban design working with the Notre Dame School of Architecture convened in Elkhart for an immersive study of the Benham area. Their four-day stay in the city grew out of conversations begun last winter when Elkhart officials and Notre Dame explored ideas together for downtown redevelopment.

As downtown Elkhart grows, city leaders project the Benham area, just across railroad tracks, will become the next hotbed for urban renewal. Residents say they’ve already been approached by developers looking to buy and flip their homes.

But in order to invest in the Benham neighborhoods and ensure current residents aren’t priced out of their homes, Greater Elkhart Chamber of Commerce CEO Levon Johnson said, the city needed a plan — something that hadn’t been done for the Benham area for decades. Having a plan in place, Johnson said, will allow the city to present their vision and ask for the funding they need to turn ideas into reality.

“A lot of times people looking at things want some big amount of money,” Johnson said, “You have to have a vision to be able to build.”

Notre Dame’s architecture school has been doing similar work for several years for cities like Kalamazoo, Michigan, LaPorte and South Bend using a charrette model. In the charrettes, School of Architecture leaders assemble a team of faculty, students and industry experts to work alongside local communities.

The team embeds in the area for several days and puts on a series of public meetings to present findings and directly ask residents what they really want in their neighborhoods. They take responses back to the university where they’ll work for several months to create a final report with specific steps a city can take to improve its infrastructure.

The program looks to work with communities where there is a need and local support for change, Notre Dame program director Marianne Cusato told Inside INdiana Business. Elkhart’s Benham neighborhood, she said, easily fit both objectives.

“Because we are an academic institution and we’re a think-and-do tank within that, we’re not just a firm that takes projects,” Cusato said. “Basically, our question list before we would enter into something is ‘Are we needed? Is it meaningful? Do they want us there and can we be successful?’ And this met all of those.”

Cusato speaks on why the Benham neighborhood fit the mission of the university’s Housing and Community Regeneration Initiative.

The team’s initial study of the Benham area this summer revealed what many already knew to be true: over time, piecemeal additions to the neighborhood — a housing authority development placed seemingly out of nowhere, a highly trafficked thoroughfare cutting through the middle of residential neighborhoods — had created a disjointed area with little walkability and no plan for future growth. In fact, the city’s current zoning ordinances, Cusato would learn, prevent it.

Many of the area’s vacant lots are narrow – measuring 35 feet across – while city zoning ordinances require a minimum 24-foot structure with a seven-foot setback.

“You’ve pinned people into a point that’s very difficult to build,” Cusato said, adding, “The city has been incredibly supportive of changing this.”

Putting plans to action

So, how does a city fix decades of mismatched policies and neglected neighborhoods?

City officials and the Notre Dame team agree, it’ll take time.

In order to get any of these projects off the ground, Elkhart officials will need to ensure the city has the proper mechanisms in place to do it. That starts with working today to revise zoning ordinances that would allow for infill housing units on vacant lots. If done correctly, the Benham area could support as many at 850 new residential units, Cusato said.

The city could work now to create a historic preservation overlay, which could save existing structures and lessen the impact of new development on current homeowners.

And, while the city is only beginning its exploration of funding sources, past precedent exists in nearby communities that can provide a road map for Notre Dame’s recommendations.

In one recent example, the Notre Dame team recommended streetscape improvements in downtown Kalamazoo, for which city officials were able to secure $12 million in grant funding. The project went so well, Cusato said, Kalamazoo officials have invited the team back for another charrette in the spring.

Nearby South Bend has been successful in attracting developers to its own low-income, infill housing projects by developing pre-approved housing plans that meet city zoning requirements.

Elkhart city leaders also have their eye on new funding made available by state lawmakers this year. A bill passed during the 2023 legislative session will make $25 million available annually through the creation of a new residential housing infrastructure assistance program.

The money can be used for projects that seek to address housing shortages and affordability, but requires interested communities to demonstrate a need through their own study to unlock funds, the legislation’s author, Doug Miller, told Inside INdiana Business.

State Rep. Doug Miller talks about how Elkhart planning could be a good fit for new state funds.

Though Miller is from Elkhart County, he said he wasn’t aware of the city’s study with Notre Dame until several weeks ago, saying it fit the mark for why lawmakers created the new housing assistance program.

“Having no knowledge of that, being able to walk in and see a 15- or 20-year master plan was huge,” Miller said of Notre Dame’s study. “I’m really proud of Elkhart for just saying, ‘You know what, the General Assembly just passed a tool. We’re gonna start thinking outside of the box.’”

Miller said he is hopeful Indiana communities can begin applying for the new assistance program, administered by the Indiana Finance Authority, by late October.

That’s good news for Benham residents like Haley, who say several years ago they feared rumors that the city would being demolishing blighted homes in their neighborhood rather than investing.

Haley, who is not a coffee drinker, said she’s ecstatic about the prospect of public art and a new, neighborhood cafe on her street — the type of place she can walk to and stop in for a cream soda or tea. The area only has one grocery store today and neighbors generally only walk to it if they don’t have another way to get there.

Haley said though she’s asked tough questions about leaving Elkhart, she’s willing to work toward a better Benham. A plan, she said, provides reason to stay.

“I hope all of this happens within the next 10 to 15 years, because it’s going to take time to build all of this,” Haley said. “These meetings were just, as they say, planting the seed, so now we’ve got to water the seed and watch the seed grow.”