Developer buys Diamond Chain site for Indy Eleven soccer stadium, mixed-use district

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

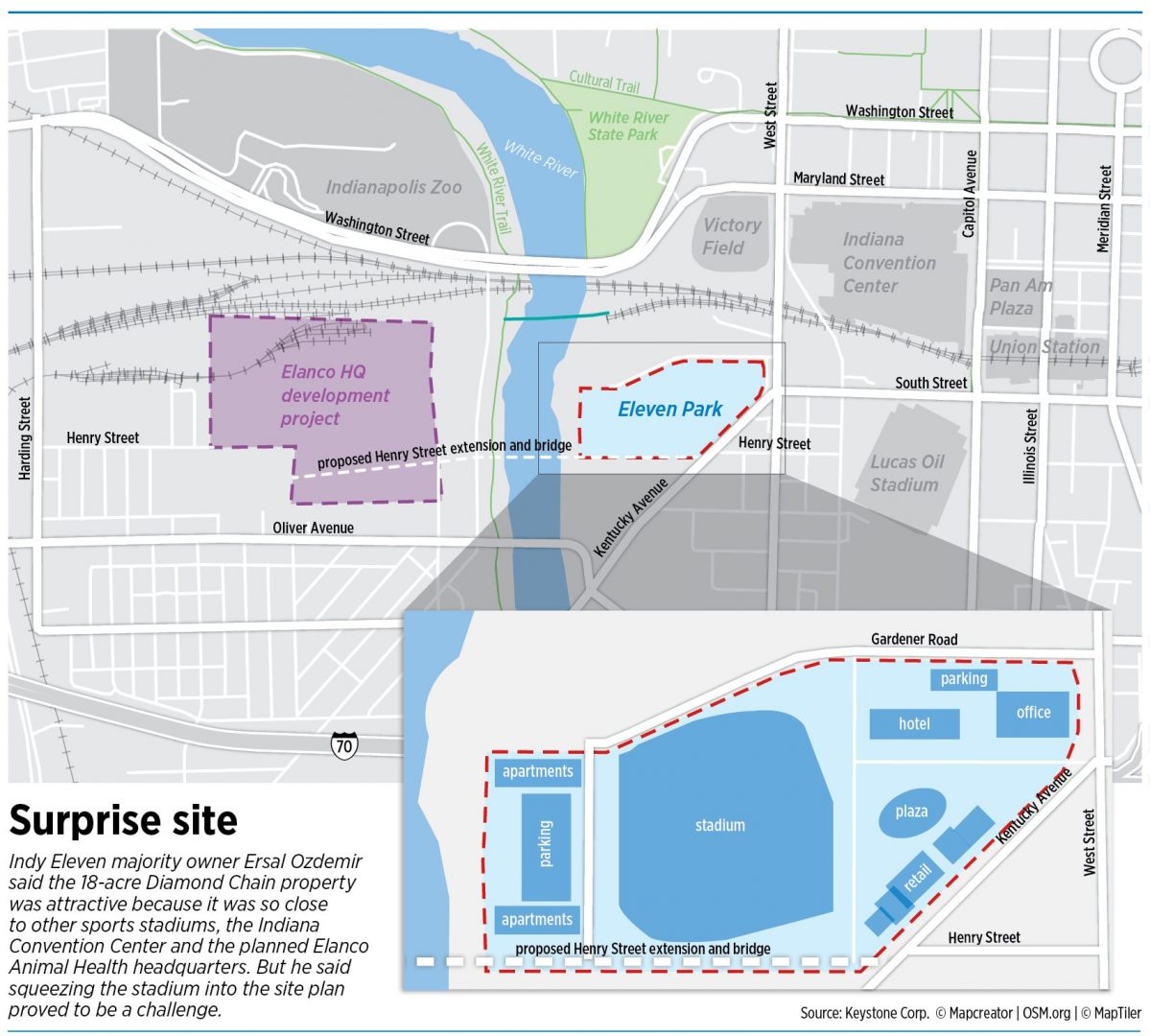

The majority owner of the Indy Eleven soccer team has purchased the 18-acre Diamond Chain manufacturing site on the western edge of downtown Indianapolis and is planning a $1 billion redevelopment that will include a soccer stadium, apartments, a hotel, office buildings and retail space.

Ersal Ozdemir confirmed to IBJ that a subsidiary of his development firm Keystone Corp. quietly acquired the site at 402 Kentucky Ave. for $7.6 million last October with the intent of locating his previously announced Eleven Park district there.

The project would be a public-private partnership with the city and state taking the lead on financing the 20,000-seat soccer stadium and Keystone developing the residential and commercial spaces. The city is expected to provide tax incentives or other financing to help fill gaps in funding.

Already, the Indiana Legislature has agreed to pay for 80% of the stadium costs through a special taxing district it approved in 2019. But the project—which Ozdemir and Keystone are still planning and designing—would need a number of zoning and financing approvals from the city and state before it could become a reality. Those negotiations will start in earnest in the coming months, Ozdemir said.

Still, obtaining a site for the project is key. Ozdemir was initially expected to announce a site in early 2021—and he told IBJ he had three different properties under consideration for months. But when the Diamond Chain site, which sits between West Street and the White River north of Henry Street, became available, Ozdemir said he switched gears.

“We believe this site is the best place to invest, knowing it will have a transformational impact [on] the south side” of downtown, Ozdemir told IBJ. The development “will serve as an important gateway to the city and bring connectivity and a pedestrian connection to the heart of downtown.”

The acquisition follows a February 2020 announcement by Diamond Chain’s Ohio-based owner Timken Co. that the manufacturing facility will shutter by early 2023, eliminating about 240 jobs.

Key to the location, Ozdemir said, is its proximity to Victory Field, Lucas Oil Stadium and the Indiana Convention Center.

It’s also just across the White River from the planned Elanco Animal Health Inc. headquarters, now under construction on the former General Motors stamping plant site. That $100 million project is expected to expand over time, with Elanco CEO Jeff Simmons predicting the area will become an “epicenter” for animal health companies. As part of that project, the state is planning to expand White River State Park along the river, and the city of Indianapolis has agreed to extend Henry Street with a bridge that will connect the Elanco campus and the state park to downtown.

“Their purchase of that site is one more really exciting component to the redevelopment happening in that area,” said Taylor Schaffer, deputy mayor and chief of staff for Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett. “It’s incredibly exciting to know that there is this much potential in the future” development of downtown Indianapolis.

Ozdemir said he expects the Indianapolis Cultural Trail will be extended from South Street to Henry Street and across the new bridge, bringing the popular pedestrian trail along the southern border of the Eleven Park site.

The organization that operates the trail has not formalized the Henry Street plans.

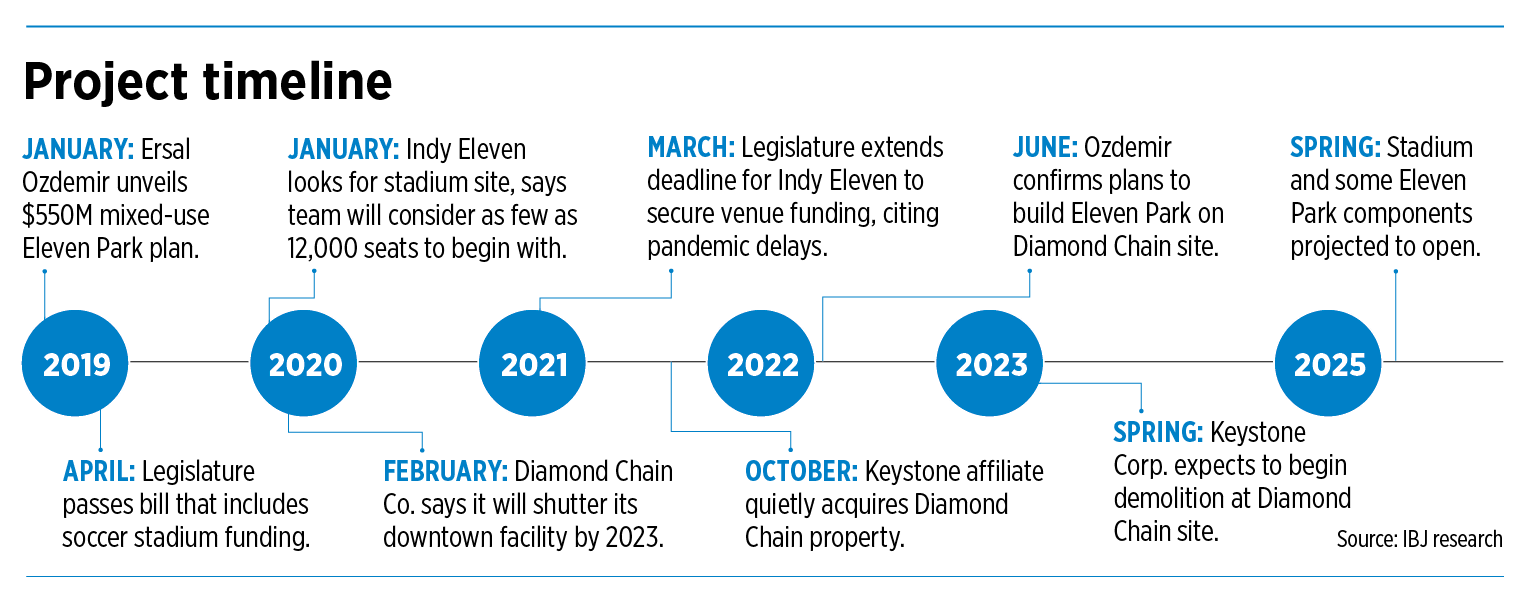

If Keystone wins approval for its plans, construction on Eleven Park could begin in early 2023—starting with the demolition of the Diamond Chain structures once the company moves out. Ozdemir said the stadium would be completed by spring 2025, in time for the team’s home opener that year.

Big step, bigger cost

The acquisition of the Diamond Chain site is the first substantial public-facing step Ozdemir has taken to advance the Indy Eleven development since securing a public funding commitment from the state in April 2019, as part of legislation that also funded renovations of Gainbridge Fieldhouse and a planned expansion of the Indiana Convention Center.

Ozdemir first unveiled plans for Eleven Park in January 2019, disclosing then that the project would likely cost about $550 million.

But now, he expects that price tag to climb past $1 billion, the result of expanded plans for the commercial components of the project and a huge rise in construction costs since the start of the pandemic.

The investment in Eleven Park “will be significantly larger than $550 million, as it gets scaled on the commercial real estate side,” Ozdemir said. “The buildings will be bigger than what [was proposed], but the stadium will be the same—we’re not changing the size of the stadium.”

In 2020, Indy Eleven officials indicated they were open to building a stadium with as few as 12,000 seats, with an expansion option later.

But Ozdemir told IBJ that he’s returned to his original plans to build the stadium with 20,000 seats. That’s despite the fact that Indy Eleven has drawn that many fans only once—at its 2019 home opener at Lucas Oil Stadium. That year, the team drew an average of 10,734 people per game—good enough for second in the 36-team United Soccer League Championship division.

This year, the team is averaging 6,050 fans per game at Carroll Stadium on the IUPUI campus.

Initially, the new stadium was expected to make up about $150 million of Eleven Park’s original $550 million price tag, but inflation means the cost of the stadium alone will likely exceed $200 million by the time of the project’s groundbreaking, Ozdemir said.

The overall project’s costs will also be driven up by plans for a larger commercial district than originally anticipated. And that could be key to making the stadium financing work.

The state has agreed to put the entire Eleven Park project into what’s called a professional sports development area that will capture taxes (including state income and sales taxes, as well as some tourism-related taxes) generated by people who live, work and shop there. Those taxes would then be used to pay off bonds to finance 80% of the stadium’s construction.

The law gives the city’s Metropolitan Development Commission the authority to establish the zone—which must happen by July 1, 2024—and the tax revenue collected for the project will be capped at $9.5 million a year for up to 32 years.

Indy Eleven is required to sign a long-term agreement with the city’s Capital Improvement Board (which will own the soccer stadium and also owns and operates the convention center, Lucas Oil Stadium and Victory Field) and pay for 20% of the stadium construction costs.

CIB Executive Director Andy Mallon said the Eleven Park announcement “is an important step in the process laid out by the General Assembly for executing this exciting project. We are encouraged by this momentum and look forward to working with the developers toward further progress.”

Financing for the rest of Eleven Park is expected to come from Keystone Corp., which will build the residential and commercial elements using a combination of equity and traditional construction loans.

The city could deploy more traditional incentive tools, such as tax abatements or tax-increment financing to support the project’s commercial components.

The city’s Schaffer said it’s too early to say exactly how the city will financially support the project. “We have been engaged in conversations with the Indy Eleven and Keystone team, but I think it’s probably too early to say what that looks like,” she said. “I’d expect those conversations to be ongoing, as the components of the project come together.”

Ozdemir said he’s not yet sure what Keystone will request in terms of funding help for the project, as those conversations are still several months away. But he expects there will be a need for additional public help.

“As the construction numbers come up, the pro formas [for tax contributions] come up, there’ll be a gap,” he said. “No project—forget about a stadium—like this could be built without a public-private partnership to do that. But we don’t know what that is at this point yet.”

Doubling down on downtown

For the past two years, Indy Eleven has intermittently teased the public with promises of updates on the project’s progress, only to delay time and again as Ozdemir has researched and evaluated potential sites. He attributed delays largely to the pandemic.

“I should be [wishing] I was in our new stadium right now, but obviously nobody could predict that a pandemic would delay us two years,” he said. “But if it didn’t, we wouldn’t have the site we do right now. So now we’re building, we’re looking toward the future.”

The Diamond Chain site was a dark horse candidate for Eleven Park, even internally. In fact, the site wasn’t available for purchase until early 2021, when Ozdemir had already narrowed down a list of 20 sites across Marion County to just three, all in the downtown area.

He declined to name those three. But sites the organization has considered include the former Valspar site west of Lucas Oil Stadium, as well as Broad Ripple High School. Ozdemir’s first pitch for a stadium, in 2014, was an $87 million project on the stamping plant site.

Ozdemir also considered Diamond Chain early on in his search, but he was met with resistance by the owners at the time. “We’d reached out to [Diamond Chain] before the pandemic, but it wasn’t available, and the owners didn’t want to sell,” he said. “Then through a process, they sold the business to another company. Not knowing what we were going to do, not knowing exactly [whether Eleven Park] is going to fit or not, we decided, ‘Let’s just go buy it.’”

Ozdemir said he made that decision in part because the parcel is one of the largest tracts of land prime for redevelopment in Indianapolis—and because of its proximity to the other stadiums.

He acknowledged, though, that the property’s shape—wider than it is deep—isn’t ideal for the stadium. Still, he thought the site overall had tremendous upsides.

“Our goal was, ‘Let’s just buy it. When they move out, we’ll tear it down, clean it up—do whatever needs to be done. Then we’ll figure out what we’re going to do with that and then work with that.”

It’s not yet clear how much—if any—environmental remediation will be required for the site. The property has a long history, including as the city’s first burial ground, Greenlawn Cemetery, and as home to the Indianapolis Hoosiers baseball club, a minor league team with multiple stints in the city.

The acquisition had some challenges, as Keystone had to buy not only the buildings, but some ground leases that had extended terms with the previous owners of the business. There was also no chance for due diligence and little room for negotiations on the price.

Ozdemir said as more information came out about Elanco’s plans for the GM stamping plant site—and the redevelopment of the White River’s western bank by the state—the more confident he became that Diamond Chain should be home to Eleven Park.

“We think it’s really important to make sure we put something there that is going to serve not just what we’re building, but be a linch point to completely transform that area,” he said. “We feel like with a project like this, there’s no better time to double-down on downtown.”

Design not done yet

While Ozdemir has made his pick for where Eleven Park will go, a full site plan and details of the project’s scope are still in the works. Even so, Keystone officials gave IBJ a rough outline of where the different components of the project will go—with a focus on keeping the stadium toward the middle of the property.

Ozdemir said he’s hopeful those designs will be completed “in the upcoming months,” alongside a complete evaluation of the project’s financing needs.

Keystone is working with three architectural firms to design the site, with more expected to join later. Populous, a Kansas City-based firm specializing in event and sports venues, will oversee design of the stadium. The company has designed several Major League Soccer stadiums, including in Cincinnati, Kansas City and Nashville.

Baltimore-based Design 3 International, also known as D3I, will handle master planning of Eleven Park. And Browning Day, an Indianapolis firm that has been involved in the design of most of the city’s major sports facilities, will be the architect of record.

“Every sports project that we do, is part of the path forward [for the city], and most of the sports projects we’ve worked on have been generational” in nature, said Tim Wise, principal of Browning Day. “So for us, this is a natural growth. It started with a sports passion that just helped us be more integrated in the city … and create a path to elevate sports venues in the city, which is part of the backbone of what Indy is.”

Browning Day has been involved in Indy Eleven’s stadium efforts since the first push in 2014. It was also part of the design team for recent Indianapolis Motor Speedway updates, the Natatorium at IUPUI, and Victory Field, as well as the RCA Dome and Lucas Oil Stadium.

Ozdemir said the Eleven’s stadium is being designed with a focus on offering opportunities for year-round entertainment, including Indy Eleven games, concerts and high school and college sporting events. He said the venue will also be available for Indiana Convention Center ancillary events.

And he said it’s likely outdoor music events too large for the Teachers Credit Union Amphitheater at White River State Park, or too small for Lucas Oil Stadium, will gravitate toward Eleven Park.

He also expects that when the venue opens, high schools and colleges will consider it for soccer championships, as well as other sporting events, like lacrosse and rugby. Likewise, Ozdemir is hopeful the venue could bring international friendlies—which are opportunities for teams to tune up for major tournaments and championships. Many new stadiums have been awarded U.S. men’s and women’s national team games shortly after they’ve opened.

The district is expected to be developed in phases, starting with the areas that will interact more directly with the stadium, such as public spaces.

Retail is also likely to be developed as part of the first phase, along with some parking components. The office space, hotel and apartments are expected to be incorporated into the project later.

“We continue engaging with architects and we’re getting engaged with more engineers on the design and demolition plans for the existing buildings,” he said. “Then we will start working [more closely] with city and state leaders to discuss what can we do collectively to make this as a special project.”

Future MLS aspirations on hold?

Right now, Indy Eleven plays in the USL’s Championship division, the second rung on North America’s professional soccer ladder, after Major League Soccer.

And while Ozdemir has aspired to take the team up to Major League Soccer ever since he launched the franchise in 2013, it’s likely to stay in the USL for the foreseeable future, given the top league’s upcoming expansion to 29 teams.

That’s in part because of exorbitant costs associated with elevating the team to the MLS and the fact that there are already a handful of Midwest teams in the league.

Ozdemir said his focus for now is on ensuring that Indy Eleven and its fans have a home of their own after years bouncing between Carroll Stadium and Lucas Oil Stadium.

“Indy Eleven, regardless of the level at which we play, our goal is to be the best in what we do on and off the field, to create the best experience for our fans,” he said. “We need a home, regardless of what we do, and we are focused 100% on Eleven Park getting done. It’s not just [about] MLS.”