Techshot to Help Grow ‘Space Lettuce’

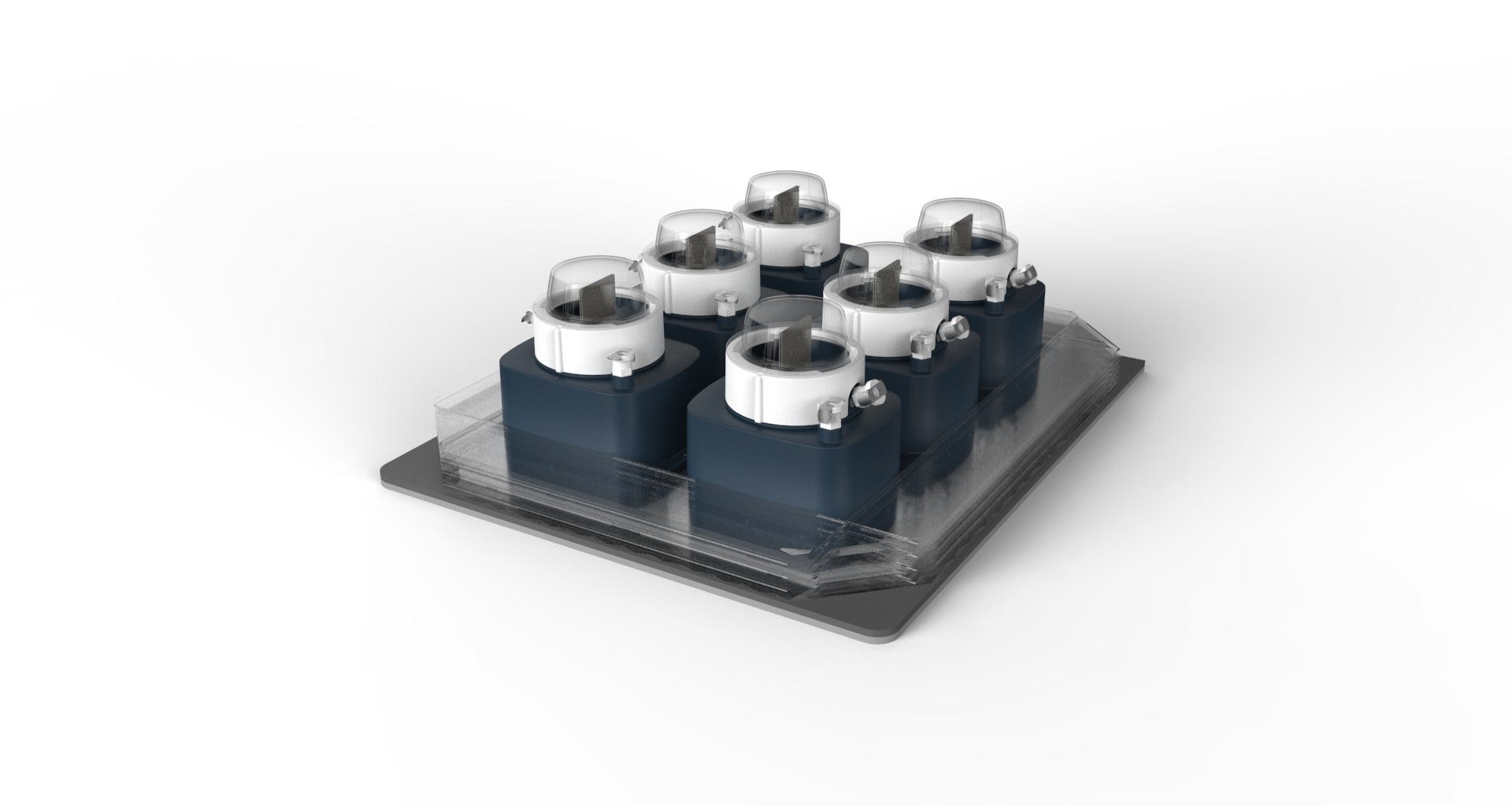

Techshot partnered with Tupperware to manufacture the system

Techshot partnered with Tupperware to manufacture the system

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA growth chamber called “Veggie” aboard the International Space Station may be small, but it has big implications for long-duration space travel, such as a mission to Mars. The Vegetable Production System could be compared to a tiny greenhouse, but for the complicating factor of microgravity. With the project hindered by making water behave in space, NASA tapped Greenville-based Techshot to redesign part of the Veggie, and ultimately, help cultivate a plan to feed astronauts on the red planet.

“No one wants to figure out after their nine-month trip to get to Mars that plants won’t grow there,” says Techshot Launch Operations Director Dave Reed. “We all liked watching the movie ‘The Martian,’ and it’s great fun to see people grow potatoes in the soil [on Mars], but it may have nothing to do with whether the potato likes the soil; it may have everything to do with whether the potato likes one-third gravity.”

NASA began growing plants and leafy vegetables on board the ISS in 2014, noting the project’s importance for not only feeding crew members, but also recycling the atmosphere and delivering psychological benefits for astronauts enduring long-term space travel. About the size of a mini-fridge, the Veggie chamber is equipped with LED lights, water and humidity controls to produce an ideal growing environment in dry space conditions.

“In order to function in a closed ecosystem, you have to ‘make as you go’ or live off the land, whether the land is an island in space or another celestial body,” says Reed. “Once we understand how plants react to being in space, then it’s a question of scale. The idea being, if you can grow a couple plants, then you should be able to grow a couple thousand plants.”

Researchers at the Kennedy Space Center designed the Passive Orbital Nutrient Delivery System (PONDS); six “plant pillows” about the size of a pack of index cards are filled with clay to hold a plant’s root structure on top of a water reservoir. But microgravity was preventing water from moving toward the plant as expected, so astronauts had to devote extra time to watering the plants daily.

“Crew time is the most precious resource flying in space,” says Reed, “because there are only so many people up there, and they only have so many hours in a week to devote to research.”

To improve watering and reduce crew oversight, NASA redesigned the system and eliminated the plant pillows. Instead, six small plant cylinders sit inside “a big box of water.” Reed likens the clay-filled cylinders to tiny flower pots with holes in them.

“The idea being, if the reservoir is quite large, you don’t have to keep adding water and can go three to seven days without adding water to the reservoir,” says Reed. “But the problem is, if you take a big box of water into space, the water doesn’t tend to stay where you want it to. It floats out of the box or goes into places like cracks or crevices.”

That’s when NASA tapped Techshot to help, because “our strength is bringing things to flight-ready status and knowing how to use microgravity to our advantage,” says Reed. The company engineered the inside of the reservoir and the plant cylinders “to take advantage of what we know about how fluids act in low gravity.”

“We can predict where the [water] will be, and therefore, the [water] will always stay in one location,” says Reed. “The real goal is to get it to function in space exactly like it would on the ground; the water should sit in the bottom of the box in both [scenarios], that way, we can predict how the plant will grow based on the water availability.”

While Techshot has the engineering expertise, the company needed a partner to manufacture a box “with a very complex geometry.” The company partnered with household name Tupperware Brands for its injection molding expertise and its ability to meet the container’s unusual specifications.

“The overarching goal is to have astronauts water [the plants] a lot less and grow full-size plants to the point they become edible—and to do so with far less crew time than what’s currently required,” says Reed. “Currently, they water them once every day or two. Our expectation is when the plants are small, they may only need to be watered every one to two weeks. Once they get very big, it might go down to once every three days.”

The Techshot-developed technology will be delivered to the ISS in the later part of 2018 as part of the Veg-04 and Veg-05 experiments. An ISS researcher plans to use the improved Veggie to grow leafy lettuce and tomatoes, cultivating new science that could feed astronauts as they venture even further in the final frontier.

Reed says the “complex geometry” of the water reservoir required Tupperware’s injection molding expertise.

Reed says Techshot worked with NASA and a fluid physics expert to develop a watering system that’s entirely passive.