IU School of Dentistry Makes Gel to Improve Root Canals

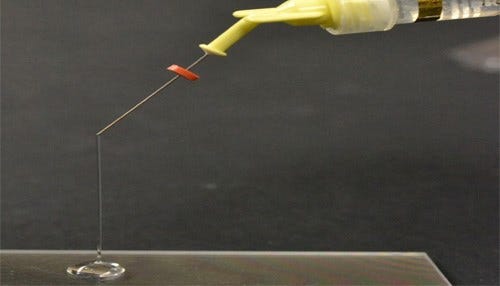

Yassen says his gel protects stem cells that conventional solutions destroy.

Yassen says his gel protects stem cells that conventional solutions destroy.

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowJust the thought of a root canal makes many shudder, but perhaps even more terrifying is a repeat root canal if the first one wasn’t effective. A researcher with the Indiana University School of Dentistry says he’s developed a gel that could increase the effectiveness of root canals. Visiting Assistant Professor Dr. Ghaeth Yassen believes his antimicrobial gel is significantly better than conventional alternatives and even encourages the tooth to rebuilt itself—a critical factor for the youngest patients.

A root canal is a treatment to repair and save a badly damaged, decayed or infected tooth; the term comes from the cleaning of the canals inside the tooth’s root. The process involves removing the middle part (or pulp) of the tooth, which contains nerves and blood vessels, because it’s infected or damaged. The dentist uses files to shape the empty canal, then washes out the chamber with an antimicrobial solution to kill any remaining bacteria, reducing the risk for further infection.

Yassen says, traditionally, dentists use a commercially available solution called calcium hydroxide or simply mix antibiotics with water to flush the chamber. This is the final step before they put the permanent material in place.

“These antibacterial materials [used to wash the chamber] only protect against bacteria the moment you apply them,” says Yassen. “They’re done as soon as you remove them.”

Yassen has developed an antibacterial gel to replace the traditional solutions; he says the gel binds to the tooth, providing up to four weeks of bacteria-killing power even after it’s washed out.

“Once you remove the gel, the effect of the gel is still there, because it binds to the hard tissue in the root and can be released over time,” says Yassen. “It can kill most of the bacteria in the root canal, which is important to keep the tooth from becoming infected again.”

Yassen notes his gel also resolves a second problem with conventional antibacterial solutions. The roots of the tooth contain stem cells that can help a tooth regenerate, but Yassen says traditional bacteria-killing solutions also kill these stem cells.

“We want to preserve [these cells], so the root of the tooth can regenerate,” says Yassen. “My gel is very cell-friendly. We’ve done a lot of studies to identify a concentration that can still kill most of the microorganisms, but at the same time, maintain and preserve the cells in the root. If we can maintain their vitality, if we do not hurt these cells, they can continue to regenerate and form part of the root—kind of make the tooth mature again.”

Yassen, who is a pediatric dentist, says the gel would be especially valuable for young patients. He’s treated many kids who have fallen and damaged their adult tooth. When this happens, the pulp of the tooth dies, but the roots aren’t yet mature. Removing the tooth or putting in an implant aren’t options, because the kids are still developing and growing. The only remaining option is a root canal.

“It’s very challenging, because the apex of the tooth is not fully mature yet. [My gel] allows some of the stem cells that are in the root canal of these kids to stay alive and hopefully regenerate a little bit—specifically with kids, when the tooth is immature. It’s basically a complete formation after the tooth becomes dead,” says Yassen. “I’ve treated these [trauma] cases for years and years, so I know how hard it can be. I want to find something that can help in these cases.”

Yassen is working with the IU Innovation and Commercialization Office to move his technology to the market. He says U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval should be swift, because the individual components of the gel are FDA-approved. A patent is pending on the technology, and Yassen believes a commercial partner is the best route to take it to the next level.

Yassen is now poised for a human clinical trial to move his discovery to patients who could take some comfort in the dentist’s chair knowing their first root canal may stand a better chance of being their last.

Yassen says the gel will be opaque, so it is visible on X-rays to guide its placement.

While Yassen designed the gel with young patients in mind, he says it could be tailored to benefit different patients.